This is fourth in a series of five articles. Access the first, second, third and fifth here.

In the long search for the Malay archipelago’s symbolic centre, the Malay polity or the kerajaan was eventually recognised by colonial administrators to represent the most evolved, sophisticated, and legible form of government in these lands. What constituted a legible political system in the Malay Archipelago was coloured by scholar William Marsden’s early 19th century study of the Malay language.

Marsden’s study is striking when considered in relation to the exhibition of the large-scale map at the inaugural address of the Society in 1878. In one particular passage, he concludes that, ‘Whatever may have been the original seat of the orang Malayu or Malays, but which the most eminent of their writers assert to have been the island of Sumatra, it is indisputable that the Peninsula which bears their name was the country in which they rose to importance as a nation, and where their language received those essential improvements to which it is indebted for its celebrity; but although its immediate influence extended on both sides of the Peninsula as far as the isthmus, where it comes in contact with the languages of the kingdom of Ava on the western, and Siam on its eastern coast, it is not to be understood that this cultivated dialect of the Polynesian is also the language of the interior.’

For Marsden, the Malay court, or the kerajaan, while originating in Sumatra, shifted its locus of power to the less fertile and uncultivated Peninsula. The crossing of the Malaccan straits, followed from the defeat of the thassalocratic Malay Kingdom of Sriwijaya, centred in the area of Palembang/Jambi in Sumatra, at the hands of rivaling Javanese Empire, the Majapahit. By various accounts, this transfer of preeminence from Sumatra to the Malay Peninsula followed the fortunes of a Sriwijayan Prince on the run. Seeking refuge first in Singapore, accounts differ whether it was the Prince or his descendents who was compelled to flee once more, ultimately settling in Malacca. Overtime, the kingdom became a Sultanate, and secured the enviable role as the most important entrepôt in the region.

While the Malay court drew spiritual legitimacy by tracing its genealogical origin back to Sumatra (though ultimately to the Macedon ruler Alexander the Great), they nevertheless produced new diplomatic currency through centering Malacca as the Ur-Malay court institution. Unlike the role that courtly institutions perform within the modern nation-state, today, the Malay court was not all ceremonial even when elaborate ceremonies contributed to the court’s cultural capital. It wasn’t essentially a theatre state, a concept which anthropologist Clifford Geertz introduced to describe polities, such as Balinese kingdoms, where aesthetics possess discursive primacy through which ‘power served pomp, not pomp power.’

Instead, the Malay court was a commercial enterprise. The Sultan was also the nakhoda, the ship’s captain. The court spoke fluently in the language of traders and its prestige rested on its ability to foster lively trade through capable and efficient running of the bandar or the pangkalan. These two forms of port constituted the urban settlements of a Malay Sultanate. In many ways, these are environments where meaningful forms of contact would have been established for many early traders arriving from Europe.

These relationships would colour what forms of government that European traders recognise as possessing sovereignty in these parts of the world. In a sense, Marsden’s scholarship came out of these past encounters. The consolidation of what is Malay in the European knowledge system would also be coloured by the new science of race that began to emerge in the late 18th century. To an extent, the colonial office in the 19th century merely extended the logic of Marsden’s narrative since the colonial office was also bound by the legal rationale of post-Enlightenment Europe, in which a nation could only conduct diplomatic relations with a political system that it could recognise as a nation. The implication was that the Malay court was thought to be the sole political system that possess sovereignty over the Malay Peninsula. Therefore, even if the peninsular was occupied by numerous Sultanates, the recognised polities were structurally similar enough to one another.

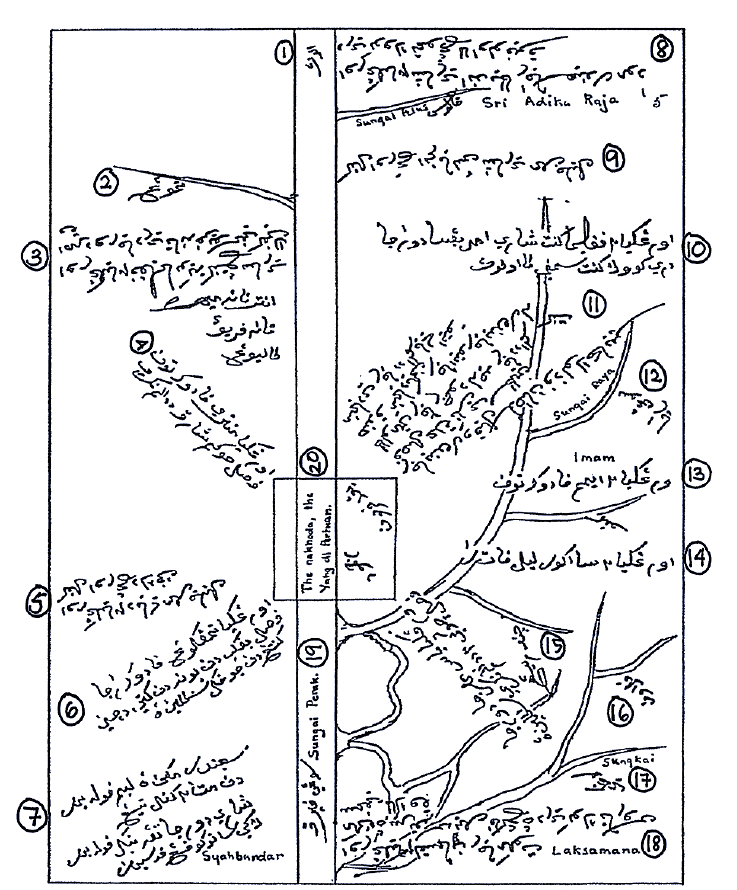

In a rare Malay map of the Perak Sultanate that dates to 1876, we are able to read a different dimension as to the extent of a kerajaan’s reach.

The translations of the map are below.

| 1. Ulunya : upper waters (of a river), up-country, the interior of a country 2. Temong (“Temong”) 3. (Upside down) Orangkaya2 Panglima Bukit Gantang Seri Amar Dewaraja dari tanah Grik sampai ke paya laut / Noble Chief of Bukit Gantang from the land of Grik to the sea swamp. Antara tanah <. . .> tanah Periuk Keling / Between the land of <. . .> the land of Periuk Keling 4. Orangkaya menteri paduka tuan pasal hukum syarak didalam negeri / Noble Minister of His Royal Highness regarding the syariah law in the state 5. Orangkaya2 <. . .> Maharajalela kapal orang d.k.p.t(n?) / Nobleman <. . .> Maharajalela ship people 6. Orangkaya Temenggung paduka raja pasal <. . .> dan bunuh dan <. . .> / Noble <. . .> Admiral of His Royal Highness regarding killings and <. . .> 7. Syahbandar <. . .> lima puluh bahara dan mata2 kapal <. . .> Seri Dewaraja tiga puluh bahara / Harbormaster <. . .> 50 bahar and ship spies <. . .> Seri Dewaraja 30 satu kupang pada sebahara/one kupang for each bahara 8. Orangkaya2 Seri Andika Raja Syahbandar Muda dari Kuala Temong ke Ulu Perak. Sungai Alas / Noble Seri Andika Raja Junior Harbormaster from Kuala Temong to Ulu Perak. Alas River (in Roman alphabets “Sri Adika Raja,” “Sungai Alas,” “5”) | 9. Kapal Orang Enam Belas Seri Maharajalela / Ship of the 16 nobles of Seri Maharajalela 10. Orangkaya2 Panglima Kinta Seri Amar Bangsa Dewaraja dari Kuala Kinta sampai keulunya / Noble Chief of Kinta Seri Amar Bangsa Dewaraja from the estuary of Kinta to its source ( ulu: upriver) 11. Raja bendahara wakil sultan <. . .> pasal adat negeri sekalian. Kalau mati raja <. . .> raja di dalam hendak menjadikan raja itu raja bendaharalah menjadi raja didalam balai itu. Kinta./ Royal Harbormaster representative of the sultan <. . .> regarding the traditions of the state. If the king dies <. . .> in the process of making that king, the Royal Harbormaster should be the king inside the hall. Kinta. 12. Sungai Raya (“Sungai Raya”) / Raya River 13. Orangkaya2 Imam Paduka Tuan. (“Imam”). Kampar. / Nobleman Imam Paduka Tuan. Kampar. 14. Orangkaya2 <. . .> 15. Orangkaya <. . .> Maharaja Dewaraja pasal cukai2 didalam negeri sekalian. Chenderiang / Nobleman <. . .> Maharaja Dewaraja regarding tax inside the entire state. Chenderiang 16. Palawan (“Palawan”) 17. Sungkai (“Sungkai”) |

Even if we were to put aside for a moment historian Barbara Andaya’s nuanced explanation of the difficulty the Perak Sultan faced in his dealings with semi-autonomous upriver ‘orang kayas’, the map is revealing of the geographical extent to which the Perak Sultanate wielded political power. Insofar as the Malay polity was structured along the riverine system, what was beyond the river were terrains that the polity could not assert sovereignty over. Instead, power was obtained through the control of rivers as passages to convey trade product and jungle produce down downriver.

With the Perak river depicted as a vertical band that cuts straight down the middle of the 1876 map, where smaller, irregularly shaped, sinewy bands are then seen to branch out from, the graphic reinforces the band’s centrality in the cultural system described by this map. Rendered two dimensional, the image of the riverine system also takes on an arboreal shape. The Perak river is in this sense the trunk, with the tributaries as branches. The image of the river as a tree provides a fitting metaphor for the power dynamics at play. With the Sultan as the trunk, the branches are domains of his immediate subordinates, carved out from the Perak river’s tributaries. Nevertheless, these branches are also jealously guarded fiefdoms with sufficient political capital to keep the Sultan’s power in check.

The kerajaan was the sole sovereign political system that was legible to the British in their attempt at securing land resources that were in demand on the global market. Therefore, it was the only polity that was recognised to have dominion over the land. This recognition would have repercussions that continue to shape how we understand political power today. One of the consequences was that the sovereignties of the orang asli over vast tracts of forested land prior to large-scale late 19th-century colonial encroachment inland was not even recognised within a civilisational framework on which sovereignty could be measured.

Consider the following statement made in 1970 by the former and current Prime Minister of Malaysia, Dr. Mahathir Mohammed on this issue, who noted, ‘In Malaya, the Malays without doubt formed the first effective governments… The Orang Melayu or Malays have always been the definitive people of the Malay Peninsula. The aborigines were never accorded any such recognition nor did they claim such recognition. There was no known aborigine government or aborigine state. Above all, at no time did they outnumber the Malays.’

After all, the concept of the ‘native population’ under British administration was different to the concept of the indigenous. As demonstrated by a confidential report filed by Charles Prestwood Lucas for the Colonial Office in London, within the British Empire, a native is ‘the coloured man in his own home, either having lived there from all time or having immigrated, forcibly or otherwise, so as to have in past times formed or now to form the bulk of or a dominant element in the population.’

Creating this definition was important for the colonial office because it helped in determining the matter of land tenure and ultimately, the issue of citizenship. The subsequent legislation of the Malay Reserves since the 1913 enactment was the culmination of a number of large-scale changes in the Malay world that was set into motion with the gradual introduction of the Resident system from 1874 and the centralisation of colonial governance through the federation of four ‘protected’ Malay States (Selangor, Perak, Pahang, and Negri Sembilan) in 1895.

Firstly, one visible change was the near-complete loss of control over the bandar and the pangkalan, which was historically the economic power-base of historical Malay polities centered on trade. Secondly, the shift from sea to land-based economy spelled at once the confinement of the population to an agricultural class in order to supply food for the growing colonial urban settlements, and also the encroachment of these new farming communities on historically Orang Asli territories.

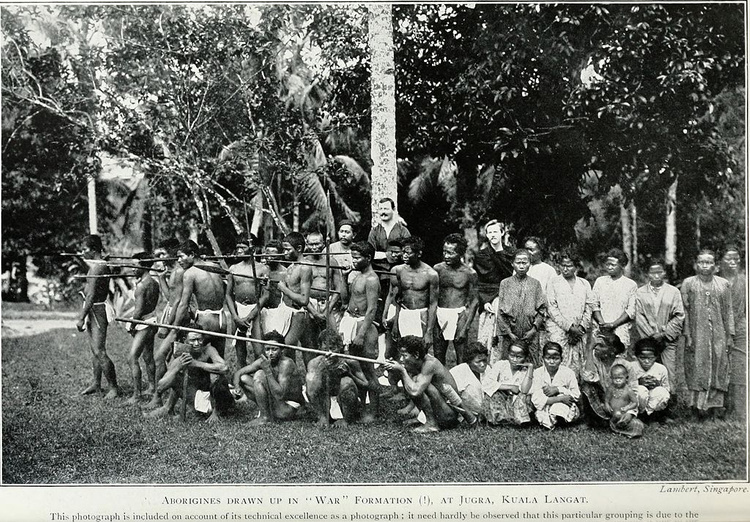

This played out as a series of displacements that would render the position of the Orang Asli peripheral within the new nation-state. In 1954, a department was created with the passing of the Aboriginal Peoples Ordinance aimed at ‘safeguarding’ the collective welfare of the Orang Asli. Deemed to be living in conditions that were ‘primitive’ [sic] on an evolutionary scale, the colonial discourse furthermore identified the Orang Asli as a vulnerable constituency.

Though recognised as ‘bumiputera’ the Orang Asli were also seen ‘a minority’ in the post-war independence movement. Population census continued to list Orang Asli as ‘Malayan’ rather than Malay up to the 1980s. Until that point, unless an Orang Asli decided to convert to Islam, they had no claim to the Malay Reserves. While the 1954 Ordinance made provisions for the creation of Orang Asli reserves, the rights of occupancy did not translate into land ownership, for the ‘pagan races of Malaya’ were thought to be incapable of owning and managing private property. Instead, they were meant to live their carefree lives under the largesse of the state.

In the wake of colonialism, the sole definition of a ‘legitimate’ or an ‘effective’ government was construed as a state polity that can be measured on ‘civilisational’ terms. These civilisational measures coloured what forms of political system can qualify as a ‘state’. These would shape the imagination of a ‘Malayan archipelago’ that had the Malay Peninsular at the centre. Malay polities were recognised as the apex cultural and political institution in these lands. Modern European cartography would also begin to describe statehood differently. Dominion was no longer a tree-like river. It came in the form of bounded territories.

To master Malay institutional knowledge and memory, the colonial project had to first locate where the mandate resided in. 19th-century scholarly endeavor did not only concern itself with applied knowledge. It encompassed the diligent and systematic study of history and culture to obtain the asal-usul of these polities. Like the orang besar/orang kaya (men of prowess/men of esteemed wealth), the Kalinga textile merchants, the Bugis mercenary warriors, and the Hadramis religious teachers, all of whom preceded the British in their engagement with Malay political institutions, the point was never to topple the figurehead but to exercise political power by means of indirect rule.

This is fourth in a series of five articles. Access the first, second and third here.

Sources

British Archives: CO885/19/7. Report authored by Sir Charles Prestwood Lucas.

‘Malay Reverves Enactment’ in Department of Director General of Lands and Mines. Ministry of Water, Land and Natural Resources. Available online at: https://www.jkptg.gov.my/en/panduan/senarai-undang-undang/akta-enakmen/enakmen-rizab-melayu

Charles Otto Blagden and Walter William Skeat. 1906. Pagan Races of the Malay Peninsular, Volume II. London : Macmillan and Co., limited.

Mahathir Mohamad. 1970. The Malay Dilemma. Singapore: Times Books International, 162–3, 170.

Further Reading

Barbara Watson Andaya. 1979. Perak, The Abode of Grace: A Study of an Eighteenth-Century Malay State. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press.

Diana J. Carroll. 2019. ‘William Marsden, The Scholar Behind The History of Sumatra William Marsden, The Scholar Behind The History of Sumatra’ Indonesia and the Malay World 47:137, 66-89.

Eng Seng Ho. 2013. ‘Foreigners and Mediators in the Constitution of Malay Sovereignty’ Indonesia and the Malay World 41:120, 146-67.

Husni Abu Bakar. 2015. ‘Playing along the Perak River: Readings of an Eighteenth-Century Malay State’ Southeast Asian Studies, 4:1, 157-197. Available online at: http://hdl.handle.net/2433/197736

Katherine Gosling. ‘Bahasa’ Malay Concordance Project. Available online at: http://mcp.anu.edu.au/papers/rtm/gosling.html

Leonard Andaya. 2002. ‘Orang Asli and the Melayu in the History of the Malay Peninsula’ Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 75:1, 23-48.

Rusaslina Idrus. 2011. ‘Malays and Orang Asli: Contesting Indigeneity’ in Melayu: Politics, Poetics and Paradoxes of Malayness, Maznah Mohamad and Syed Muhd Khairudin Aljunied (Eds). Singapore: NUS Press, 101-123.

Rusaslina Idrus. 2011. ‘The Discourse of Protection and the Orang Asli in Malaysia’ Kajian Malaysia 29:1, 53–74.