This is the concluding article in a series of five articles. Access the first, second, third and fourth here.

One of the unrealised goals of the Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society was to establish a library that would amass as complete as possible a collection of books written in the Malay and kindred languages. By mastering all branches of Malay knowledge, the British colonial enterprise had the design of absorbing the Malay states into its imperial fold.

Knowledge not only contributed to the material extraction of resources. More significantly, imperialism was fueled by an insatiable ambition to collect worlds. Only by mastering its ‘worldview’, could the British claim political legitimacy as the successor of Malay rule over these territories. This was not dissimilar to how the British Raj fashioned themselves as the inheritors of the political mandate over India from the Mughal Empire.

Yet cracks began to gradually emerge. Over time, the library was to become increasingly ‘unmanageable’ in size. Cultural knowledge is after all an esoteric field of inquiry. With the pacification of the territories on the Malay Peninsular now under both direct and indirect British rule, branches of knowledge that did not immediately contribute to the economic progress of the imperial system were also viewed as quaint, worthy of mere curiosity.

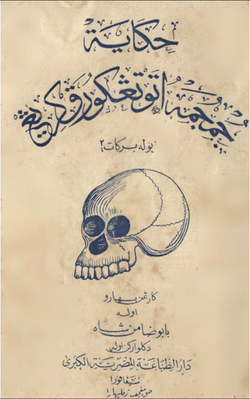

Babu Zamansyah, Hikayat Tengkorak Kering Boleh Berkata-Kata Tengkorak itu Asalnya Daripada Sultan Jumjumah, early 1920s

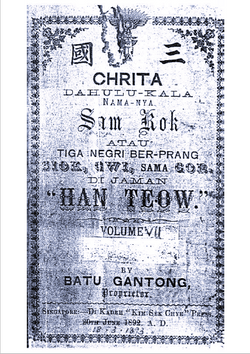

Batu Gantong, Chrita Sam Kok Vol VII, 1893

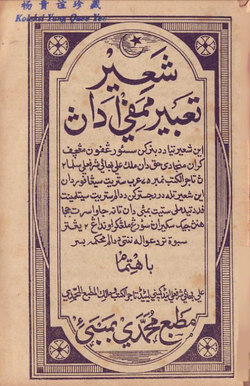

Syair Tabir Mimpi, early 20th century

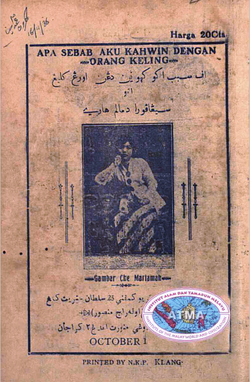

Raja Mansor, Apa Sebab Aku Kahwin Dengan Orang Keling, 1936

Hikayat Perjumpaan Asyik, 1927

Ali, Syair Tabut, 1864

The manuscript collection was eventually transfered to the Raffles Library in 1923, which is today under the custodianship of the National Library Board of Singapore. From the outset, the Society’s collecting policy was riddled by a contradiction of terms. On the one hand, there was a desire to clarify and locate the unadulterated source of what constitutes ‘Malayness’, in the belief that arriving at this authencity would confer mastery over language and control over discourse. On the other hand, to be a library of all Malay written sources meant it had to also be eclectic and voracious. The stakes were high, given that the British were also competing against the neighbouring Dutch in the East Indies over the mastery of the Malay language, albeit for slightly different design.

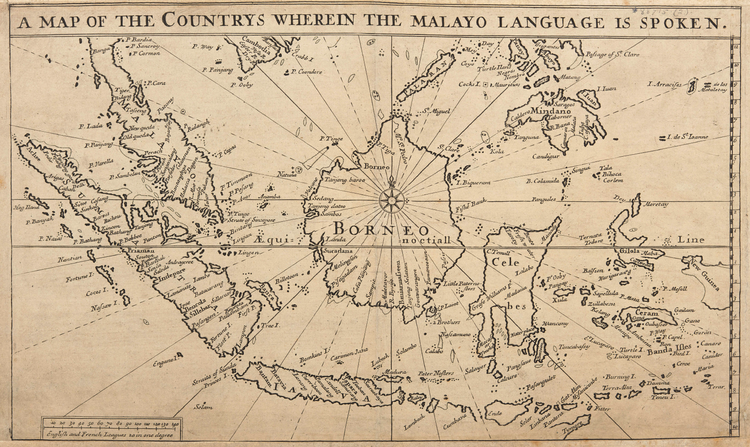

Both colonial power were nevertheless in accord on where they thought the object of their learning reside – the Johor-Riau Sultanate. The competition resulted in splitting of the Sultanate into two halves with the signing of the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824, a thin pencil line of division that was drawn up in London, without the inclusion of any competing parties to the Johor-Riau Kerajaan. In promoting a Malayan-centric map of the archipelago, the Society produced an entrenched hierarchy of relations between Straits of Malacca as centre of the Malay World and the rest, court Malay as authentic and the bazaar Malay as creole, and the primacy of a centralised institutional Johor-Riau court Malay as the defining characteristic of the archipelago over a more rhizomatic concept of Malay as a language that facilitated transactions and encounters.

While recognising the contextual particularities of Malaya’s vast geographic expanse, Hose suggests that the nomination of the term ‘Malaya’ to stand for the Malay archipelago is useful because it was ‘being at once the most simple, and the most intelligible.’ More importantly, he argued that the Malay language or ‘some closely allied form of speech’ was extensively the area’s lingua franca – because it was a language that facilitated commerce.

It is on this point that the contradictions of imperial statement becomes apparent – a sovereignty that was recognised as politically legitimate had to be measured using civilisational markers and values determined by European conventions and legal frameworks. This line of reasoning is repeated by post-independence state-historians like the late Khoo Khay Kim who insisted on this subject as an irrefutable fact rather than something that should be subjected to critical discussion.

Ultimately, by insiting such a definition of political legitimacy can only be construed as a fact served to strengthen the legitimacy of the postcolonial nation-state as a successor of the colonial state. Without de-colonising the very concept of political legitimacy, the nation-state inherited a classical liberal colonial mandate that can only insist on recognising political legitimacy within a civilisational discourse, while excluding other forms of sovereignties or organisational approaches.

Where do excluded political will end up? They end up in dreams, dreams that form everyday words that enable conversations. They exist in different sites – the keramat shrine, the bangsawan theatre, the parks and gardens, the cinema, the school, the jungle, the streets, the books, the private bedroom, the opium den, the brothel, gambling den and the tollbooth. They exist in painting, epic poem, embroidery, photographs, music, drawing, dance, drama, radio, graffiti, and fingerprints. They abide in places where one could retreat into and dwell in another dream.

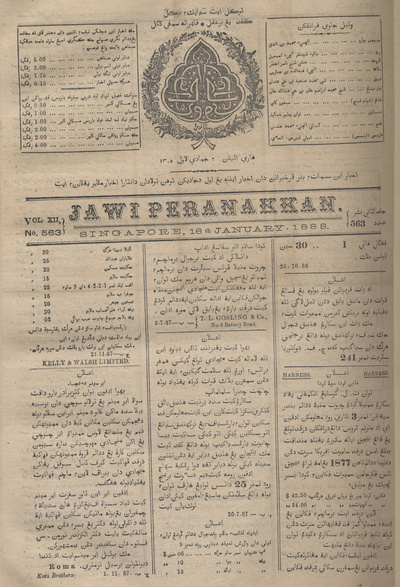

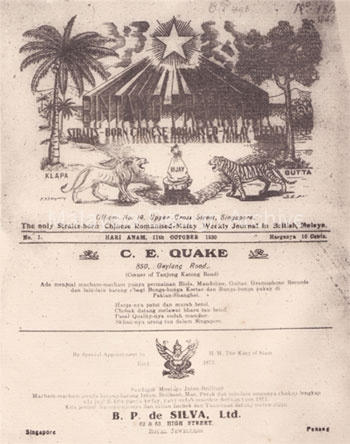

If there was a lingua franca of the region, the Melayu language that was described as the common denominator – that builds bridges, connects people and finds new way to circumvent old habitual ways of expression so that it gains new currency with the changing time – was not just a court language with its ceremonial display of effusive civility masking the conflicts and intrigues that are the stuff of nightmares. More importantly, Melayu was a language of traders. Who can adjudicate that the bazaar was no less authentic than the realities of the court? Or no less moral, no less sophisticated, no less cosmopolitan?

In this sense, the shadows and shades of William Marsden, the early 19th century scholar of the Malay archipelago, continues to loom large. In his essay ‘Melayu and Malay — A Story of Appropriate Behavior’, literary scholar Henk Maier suggests that rather than reject Marsden’s thesis, it is in Marsden’s body of work, we might discover the deconstruction of Melayu:

‘Marsden’s shadows: Malay is the language of the Malays who live on the Peninsula where the variants can (and should) be reduced to a uniform and genuine form that conjures up a distinct race or nation and a distinct culture, radically different from the others around them.

Marsden’s shades: Malay is the language that has constantly been expanding its reach and effects in and beyond the Peninsula by way of differentiating dialogues; it has been used by “people” who are evoking and confirming elements in a constantly heterogeneous aggregation of notions, ceremonies, and ideas by way of their sentences and words, together shaping and reshaping Malayness, Melayu.’

In a marketplace of dreams, stories, goods, Gods, ghosts, medicine, demons, hopes and despair, the colonial state soon realised they were always in free competition against other sovereignties. That of your kelings, orang2 asli, dayaks, wong2 cilik, chinaman, arabs and habshis (africans), momoguns , along with your rakyats and pranakans – all of them also traded their stories and ‘threw shades’ in the bazaar register of Melayu.

In an analogous mode of discourse, Paul Kratoska’s pithy observation on historical realities offers another entrypoint:

‘The reality of Malaysian history, like the reality of the history of any other country, is that it consists of the activities of ordinary people earning a living, feeding their families, raising and educating their children, seeking amusement, falling ill and getting well, and as a rule avoiding the government whenever possible.’

These realities are necessarily spaces of interaction, where the conventional rules of language cannot but ultimately break down, and communication must always begin by scrambling together the made-up, the make-shift, the misinterpreted, the spontaneous, and even the inexpressible. It is by paying attention to these creole spaces of encounter that we enact a counter-cartography – to recognise identity, when it is imagined, as constituted amongst others. Within these spaces of putatively imperfect communication, we learn through encounters and accommodations that transform the self and its relationship to the other. This is the chief object of our inquiry.