Meet Mr. Koh

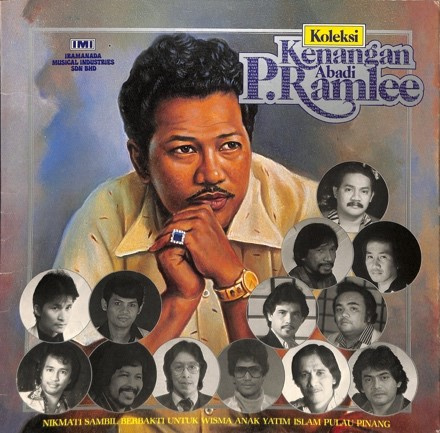

During my internship at Malaysia Design Archive, I stumbled across MDA’s collection of the graphic designer Koh Lee Meng’s work from the 1980s to early 2000. The works were incredibly extensive, from restaurant menus, logo designs, corporate profiles, and – what really amazed me – his designs of record sleeves. As a graphic design student myself, I was incredibly impressed with his precise craft of logotypes, something very rare to see nowadays. It was a hidden gem indeed. These were Malay record sleeves from the 1980s, emblazoned with household names like P. Ramlee. The design was distinctive, kind-of-retro and was unmistakably influenced from Western records, yet it had an unmistakably Melayu taste. It felt authentic in its own way.

In person, Koh welcomed me warmly and generously – despite my nerves – as he shared stories from his early graphic design career and thoroughly talked about his creative process, craft, and experience. His consistency, passion, and resilience surely were the secrets behind the more than thirty years he has had in the industry.

Koh’s early interest in graphic design was influenced by comic books, movie magazines, and the visuals he saw around him. At an early age, he aspired to be an art director, which led him to study Fine Arts at Kuala Lumpur College of Art. Koh became an art director two or three years after he graduated from Colchester School of Art in UK. Afterward, in 1984, he started Koh Design Consultants, which was based on the mantra “We Communicate by Design”. KDC started in branding, print, packaging, and has since expanded to wayfinding and signage.

In Malaysia in the 1980s, the term ‘graphic design’ was rarely used. Many called themselves commercial artists, and it wasn’t recognized as a profession, nor was it a career path as popular as it is now. There weren’t many art schools as well. As the creative industry was dominated by advertising and public relations companies, Koh learned from their high standards and met clients from the industry as well. The difference was advertising prioritized sales, while graphic design’s goal is effective communication. It was Koh’s desire to advocate for graphic design as a profession and to convince his clients of the value of graphic design as a marketing tool.

The 12-inch Record Sleeves

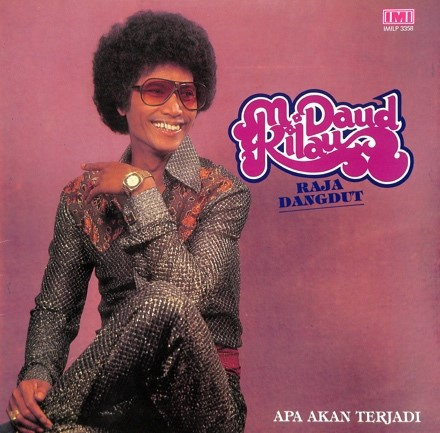

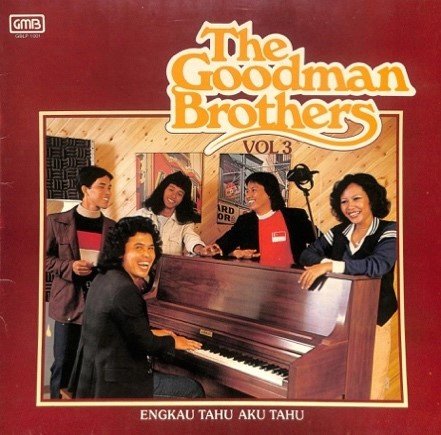

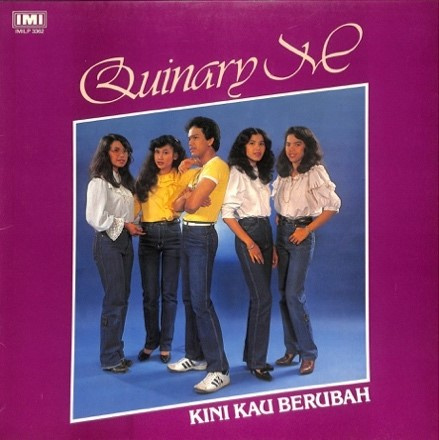

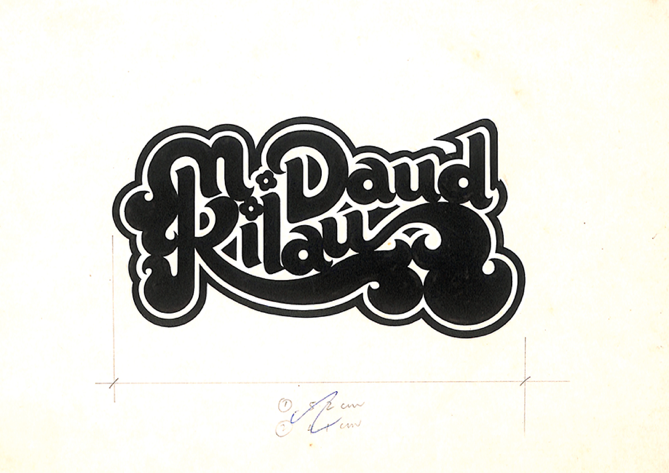

One of Koh’s most interesting projects in the 1980s was record sleeve art. He designed sleeves for Malay artists such as M. Daud Kilau, P. Ramlee, A. Ramlie and The Goodman Brothers, including designing the logotypes, layout setting, and colour adjustment. In our conversation, he mentioned that his sources of inspiration were the lyrics of the music, current trends, as well as past record sleeves’ designs. Trends dictated that record sleeves would be dominated by photographs, so he discussed with music labels what angles to shoot from, and what outfit colours would suit the style and music genre of the artist. Though record sleeves can be seen merely as another a form of packaging, the visuals communicate the mood and theme of the music towards a specific target audience. It is an art that stands as the genre of music that differentiates one from another1, as well as reflecting the character of the artist or musician. Thus, record sleeves themselves should be seen as a graphic identity. To this day, people still seek record sleeves as a treasure: it is not only nostalgic, but also is a part of how one is meant to experience music.

“Generally, you can see those days all albums are just very straightforward,” Koh said. He also expressed that he could’ve done so much better, but it was always pleasant to look at the logotype he crafted. Mostly, Malay record sleeves in the 1980s were agreeably straightforward, as the main visual was either photographs or illustrations of the musical artist. This trend for photographs as album covers started in the West in the 1950s, then progressed to bold typography. In the 1970s, there was a rise in fashion photography, ushering in an era of logos and mascots. Distinctive logos for artists surged, most notably with logos for heavy metal bands such as Led Zeppelin, Motörhead, and Def Leppard that “turn[ed] bands into brands” (Chilton, 2019). All this led to the design trend of using photographs – from close-ups of faces to full-body shots – as the main imagery of albums, accompanied by logos to mark the brands of the artist. One thinks of the record sleeve of Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours, which has a similar approach to these 80s Malay record sleeves. Despite global influences, Malay record sleeves still maintained their distinctive and authentic Melayu flavour by maintaining a similar style with pop Melayualbum covers in 1975.

The straightforward approach in the design of these record sleeves is actually in harmony with Dangdut music, where, as Wallach writes, the “story narratives tend to be simple and straightforward.” Certain approaches depend on the genre of music it represents, feelings it want to transfer, and saying certain message like political or social issue. As much as the design of the sleeves have a straightforward approach, they don’t explicitly displays the message of the music. Functionally, the record sleeves exist to represent the music but still leaves space for viewers to raise questions and perceive it individually.

Vaughan Oliver, in-house designer of record label 4AD, once said that record sleeves are the “gateway into what the music is about without defining it but also providing a suggestive mood and atmosphere.” Similarly, romantic and cheerful moods for Malay record sleeves were shown through fashion, colours, and typefaces that were retro-disco influenced, with designs that mirror the industries of fashion and style, such as M. Daud Kilau’s flamboyant outfit, bold-patterned shirt, flare pants and afro. The genre of Dangdutis rooted in orkes melayu (Malay orcherstra)and influenced by Indian and Islamic flavour. A Dangdut ensemble typically consists ofkeyboard,electric guitar, drum, seruling (flute), and violin. Its lyrics usually express a melancholic, ruminant mood that comments on social and personal hardships that “represent the innermost feeling of us all.” As an example, M. Daud Kilau’s Aku Merindu lyrics go:

Siang dan malam hati gelisah

Kasih menghilang tiada berita

Entah dimana dikau menyepi

Tinggalkan daku seorang diri

Wahai kasihku datang padaku

Aku merindu padamu selalu

Agarkah hilang resah di jiwa

Bila bertemu duhai kekasihku

Aku merindu

My heart is restless on day and night

My lover is gone without a word

Who knows where you are

Leaving me all by myself

Oh my lover do come to me

I miss you dearly

So will my soul’s trouble be gone

If I meet you, oh dear love

I miss you

The in-rhyme lyrics, repeated words, and similar tunes over and over has a meditative quality, but at the same time its repetition forces one to dwell in its emotion: we can’t get over it. The use of words like merindu(missing), resah (troubled), and kekasih (lover) express a deep longing towards the lover. It conveys the sadness of not being together. The song’s romantic melody is depicted through the visuals of dominant pink colour and flower elements on M. Daud Kilau’s outfit and logotype. Despite the romantic and happy visuals, beneath the surface is deep sadness speaking through the lyrics.

The logotype of M. Daud Kilau, as Koh says, “depends on how we imagine M. Daud Kilau… he is very flamboyant, eclectic.” As M. Daud Kilau is a dangdut singer, the logo gives a romantic, sweet mood through the tails branching from the letters and flower symbols. By understanding those characteristics, adapting to current trends, then translating it through the swirl and flair of the typeface, the logotype was already speaking for the musical artist. A logotype “communicates feelings, emotions, and vital nuances of the written word.”9 Since, there were no computers then, Koh drew the logotype by hand. Seeing it now, the art is so precise you might’ve not believed it was hand-drawn. These skills in craft mustn’t be forgotten.

With the contemporary proliferation of LPs and EPs, demands for the graphic design of album art are higher than ever. With that, the role of graphic designer and advertising sometimes got mixed up. Advertising uses any means possible to achieve sales, meanwhile, the focus of the graphic design is on successful communication by using the right medium. Record sleeves tell a story of history, visual culture, fashion, and of course, music from a specific time and place. Design will always be a part of music, as a reflection, message, and a medium to communicate. Visuals that are constructed of color, logo, photography, and texture are responsible for a first impression to the public. That is the role of graphic designers: to utilize mediums to communicate effectively, or as Koh Lee Meng would call it, to be effective “visual communicators.”

The Koh Lee Meng collection is available to view at Malaysia Design Archive and through our online repository, http://search.malaysiadesignarchive.org. The archive consists of works by Koh Lee Meng from the 1980 to early 2000, during his career as a graphic designer and his practice in Koh Design Consultants.

Bio

70s Disco Fashion: Disco Clothes, Outfits for Girls and Guys. (2018, March 20). Vintage Dancer. https://vintagedancer.com/vintage/70s-disco-fashion/

Bestley, R. (2008). Spin/3 Magazine: Action Time Vision. Spin/3 Magazine: Action Time Vision.

Chilton, Martin. (2019, September 2). Cover Story: A History of Album Artwork. uDiscoverMusic. https://www.udiscovermusic.com/in-depth-features/history-album-artwork/

Donwood, Stanley. (2020, January 24). Sleeve Art. The Times Literary Supplement. https://www.the-tls.co.uk/articles/sleeve-art-essay-stanley-donwood/

Koh, Lee Meng. (1981-1983). [Record Sleeves]. Koh Lee Meng Archive, 1980-2002, Malaysia Design Archive, (Box 18, Folder 3), Malaysia.

Muttaqin, M. (2006). Musik Dangdut dan Keberadaannya di Masyarakat: Tinjauan dari Segi Sejarahdan Perkembangannya (Dangdut and Its Existence in the Society: The Review of Its History and Development). Harmonia: Journal of Arts Research and Education, 7(2).

Ooi, Keat Gin. (2009). The A to Z of Malaysia. Scarecrow Press.

Osborne, R. (2014). Audio books: the literary origins of grooves, labels and sleeves. Litpop: Writing and Popular Music, 201-215.

Kang, Siew Li. (1996, August). Giving graphic designing the recognition it deserves. Business Times. p. B17

Ponnampalam, Andrew. (1995, March). Upward path of a graphic designer. New Strait Times. p. A1

Whitehouse, Matthew. (2017, February 17). art on your sleeve: the definitive history of the 12” record sleeve. i-D magazine.https://i-d.vice.com/en_au/article/neng7k/art-on-your-sleeve-the-definitive-history-of-the-12-record-sleeve

Kilau, M. Daud. (2007). Memori Hit M. Daud Kilau. [Audio]. https://www.deezer.com/us/album/116145202?autoplay

Wallach, J. (2014). NOTES ON DANGDUT MUSIC, POPULAR NATIONALISM, AND INDONESIAN ISLAM. In Barendregt B. (Ed.), Sonic Modernities in the Malay World: A History of Popular Music, Social Distinction and Novel Lifestyles (1930s – 2000s)(pp. 271-290). Leiden; Boston. Brill. www.jstor.org/stable/10.1163/j.ctt1w8h0zn.13