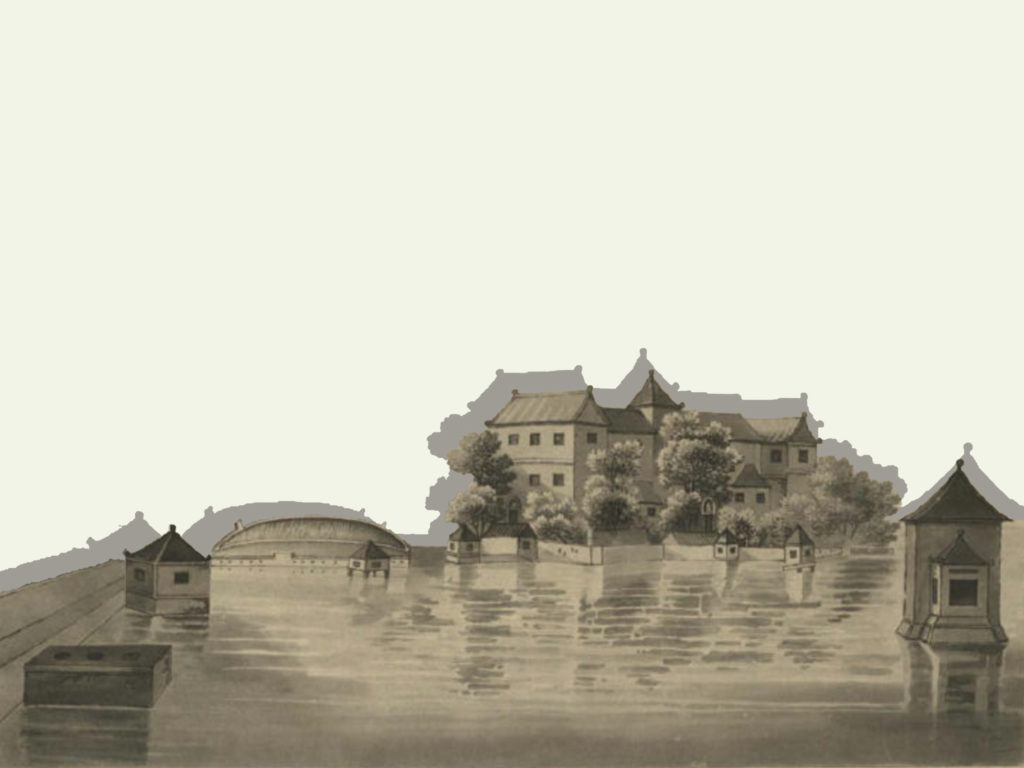

An uncoloured aquatint depicting a stately castle in the middle of a lake called Pulo Kenanga is attributed to the British artist Joseph Jeakes. Pulo Kenanga is located in Taman Sari, meaning “perfumed garden,” a vast pleasure garden founded by Sultan Hamengkubuwono I in the eighteenth century. Located in the city of Jogjakarta in the island of Java, it stretched over twelve hectares and contained over fifty structures, and was planted with various kinds of fruits, herbs and spices.

Jeakes’s picture draws our attention to the lake whose surface, revealing a distorted reflection of its environs, is the only indication of movement in an otherwise still and undisturbed setting. The lake seems to extend from the picture plane into the real space of the viewer, but the castle is far and unreachable. The ripples spread towards the viewer, like an invisible barrier of force pushing the viewer outwards and leading the castle to retreat further into the background. They disfigure and break up the mirror image of the garden into unrecognisable amorphous shapes. Jeakes’s rendition of Taman Sari, placing emphasis on the picturesque, fails to notice the cunning politics underlying the construction and use of the garden by the sultan. It tells us what is legible to the colonial gaze, and more importantly, what slips from it.

Saidian Orientalism reveals how the West had created a prejudiced representation of the East, painting their culture as one steeped in pleasure, decadence and backwardness. But Europeans, equally, indulged in pleasure. The pursuit of pleasure was, after all, what encouraged them to expand their empires to conquer new markets and trade in luxury goods. Western thinkers in the nineteenth century also embraced decadence as a corrective measure to curb progress, whose repercussions had worried them. In order to disentangle the triad of pleasure, apathy and decline associated with colonised regions, we need to consider the politics embedded in objects, sites and activities of pleasure.

Art history for the most part is concerned with visuality, but textual sources could equally evoke vivid imagery. Travel journals can help us to study a site which would otherwise be ignored because of a lack of pictorial sources.

Jan Greeve, the governor of Semarang between 1781 and 1791, met with Sultan Hamengkubuwono in Jogyakarta for ten days beginning on 5 August 1788. Consider the following description of Greeve’s visit to Taman Sari translated from Dutch by historian M. C. Ricklefs based on the governor’s diary:

“On Friday Greeve took gifts to the sultan and his women, including two silver spittoons for the sultan, rather improbably adorned with silver filigree tulips. Mangkubumi then took Greeve to see the pride of his old age, the pleasure-garden complex of Taman Sari. But not even there could Greeve take his ease. The governor and the sultan rode in a gilded boat to one of the buildings which rose out of the water. The sultan displayed a remarkable vitality for his age by climbing the steps from the water and hiding himself in one of the rooms, forcing his companions to play hide-and-seek. In another building, the old sultan began to dance and animated the entire company to join him.… Greeve must have been relieved when he was finally able to leave Jogyakarta on Friday 15 August, having extended his stay by several days to please the sultan.”

The sultan inundated Greeve with a number of activities at the garden in an attempt to exhaust and intimidate him. The governor was unable to excuse himself from the formal ceremonies for fear of offending the sultan at a time when Dutch relations with Jogyakarta were strained. One can imagine how claustrophobic the officer would have felt upon entering Pulo Kenanga. His means of escape were limited, while he had to participate in the pleasures of the sultan. The sultan was well versed in diplomacy – here he is, undermining colonial authority by taking advantage of the governor’s compromised position under the guise of pleasure.

Consider another account of Taman Sari by Eliza Scidmore, an American traveller who visited Java in the late nineteenth century. She recounted stories about the garden, gathered from locals in Jogjakarta, involving Sultan Hamengkubuwono II and Marshal Daendels, the governor-general of Java from 1801 to 1811:

“On one unfortunate day he kept marshal Daendels waiting in the outer court for an hour beyond the time appointed for an interview, while the sultan and his women made merry, and the gamelan sounded gaily from the Water Kastel’s galleries. Daendels, growing weary, suddenly pushed through the retainers to the mouth of the tunnel, and appeared to the dallying sultan in the Water Kastel without announcement or further ceremony, and with still less ceremony seized the sultan by the arm and led him back to Dutch headquarters, where the interview took place. Another version of this Water Kastel tradition describes the mad marshal as making a dash down terraces and staircases to a water-pavilion sunk deep in foliage at the edge of a tank, where, in a shady cellar of a sleeping room, shielded and cooled by a water curtain falling in front of it, he dragged the sultan from his bed, and carried him off to the headquarters.”

The garden was both a site of pleasure and tension. The stories capture a different pace and temporality percolating within the garden that breaks away from the regimented time dictated by politics. But the discrepancy between the two senses of time masks the political efficacy of pleasure. Indulgence in pleasure did not equal political apathy. Rather, we could read the sultan choosing pleasure over diplomacy itself as a political move. The Dutch needed the sultan on their side and feared that he could ally with the British who were preparing an invasion of Java.

Lacking pictorial sources which place local actors within Taman Sari, I turn to written accounts that animate the garden. Art history’s reliance on pictorial sources sometimes disfavors the study of art historically significant sites in Southeast Asia. The task of decolonizing art history demands a rethink of its use of sources. By piecing together fragments of text pertaining to the garden, we can arrive at a more nuanced picture of the garden which was disfigured by the colonial gaze. Although the travel accounts consulted in this essay were based respectively on the writings of a colonial officer and foreigner, their vivid language and placement of local actors within the narratives of the garden allow us to isolate localized forms of pleasure and their entanglement with politics. They open alternative ways of seeing by encouraging us not only to embrace the visuality of textual sources but also to imagine the local through and beyond the colonial gaze simultaneously.

Sources and Further Reading:

Fieni, David. Decadent Orientalisms: The Decay of Colonial Modernity. Fordham University Press, 2020, p.12

Ricklefs, M. C., Jogjakarta under Sultan Mangkubumi 1749-1792. London: Oxford University Press, 1974, p.304

Said, Edward. Orientalism. Pantheon Books, 1984.

Scidmore, Eliza Ruhamah. Java, the Garden of the East, New York: The Century Co., 1907, p.277

Thornton, William. The Conquest of Java. New York: Tuttle Publishing, 2004, intro