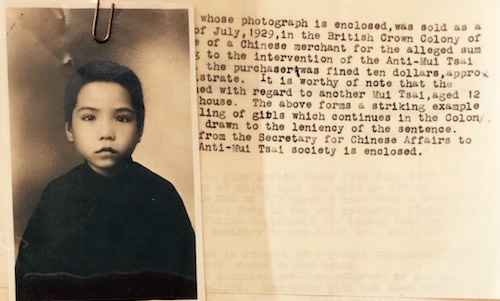

On 6 October 1870, the Chief Justice of Hong Kong Sir John Smale issued a court verdict that would stir entrenched native resistance and inaugurate protracted legal ambiguities over the regulation of the socially ingrained practices related to mui tsai in Chinese households. Smale tried a few individuals convicted of engaging in the human trade of Chinese girls, specifically condemning it for contravening the freedom of persons that none could sell his own person into slavery. Smale’s edict angered the Hong Kong elites: local Chinese merchants immediately petitioned then-Governor John Hennessy to argue for the merits of preserving the mui tsai.

The Chinese merchants disagreed with an outright ban. They reasoned that mui tsai bondage is a patronage system in which wealthy brethren foster girls from poor households, preventing mass infanticide and starvation. They sought hard to convince the Governor to distinguish between abuses of the system and a benevolent spirit alleged to be at the core of the practice. This culminated in the setting up of the Po Leung Kok (Society for the Protection of Women and Children, PLK) in 1880. Similar institutions followed soon after in the Straits Settlements, which briefly quelled concerns over child servitude. Yet, there was no outright ban on the practice. Since its inception, the PLK functioned as an extension of the elite Chinese community’s arm. Funded mostly as a philanthropic enterprise of Chinese businessmen, the PLK enjoyed extrajudicial powers to investigate kidnapping networks, cooperated closely with the police, and most importantly according to its proponents, provided extensive care and place of refuge for kidnapped victims.

The PLK worked to “suppress kidnapping and traffic in human beings”, taking in vulnerable girls who were abused, exploited or sold into prostitution. Having dealt with over 2000 such cases in each decade between the 1890s–1910s, it might be argued that the PLK was successful in its aims. However, the introduction of the PLK did not stem solely from charitable concerns about the status of abused mui tsai. The institution could more cynically be interpreted as a one way to safeguard the continued supply of indentured, cheap labour. It also brought to the fore problems of pride, patriarchal hegemony and a jealously guarded sense of nationalism. The PLK was primarily a ploy by elite (male) Chinese tycoons to forestall the encroachment and intrusion of British colonial power. The enforcement of the law to the fullest extent, as recommended by Smale, would have endangered the Chinese tycoons’ own trade of concubines, children and domestic servants, and reduced their political power significantly.

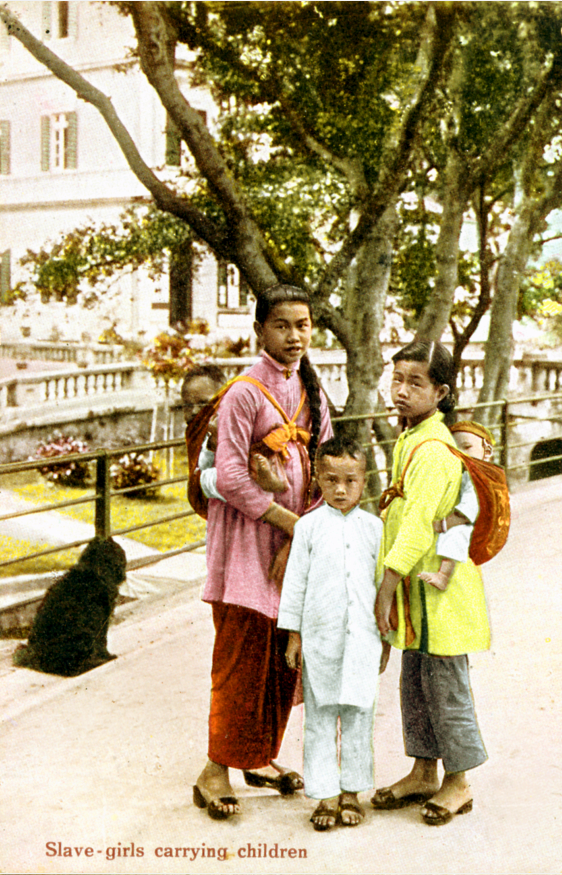

Due to the lobbying power by elite Chinese, the mui tsai system persisted on the grounds that these were ‘legitimate’ adoptions and were part of a domestic convention built around the practices of concubinage and maintaining brides-in-waiting, all of which the Chinese community insisted were treasured traditions. The introduction of PLK forestalled further reformists’ attempts to abolish the mui tsai system. After all, the term mui tsai, loosely translated as ‘little daughter’, allowed multiple ambiguities to traffic under a charitable guise of the provision of foster care. The argument that mui tsai bondage is a traditional custom found its loudest support among Orientalists, who declared it inconceivable to think that women enjoyed “individual relations apart from the relations of the family” and argued that mui tsai were better off within the household of a patriarch. According to contemporary defenders of the practice, the mui tsai was a role that was introduced into the household in an equitable relationship as the “hired domestic”, “the wife” and the patriarch’s “own son”, further framing the practice as a mutually beneficial system of social support infrastructure.

After Chief Justice Smale’s short-lived campaign, the bondage system attracted powerful reformist opposers, including the Social Science Association, Society for the Protection and Aborigines, Anti-Slavery Society and various missionary groups. While campaigning ostensibly for the welfare of the mui tsai, anti-mui tsai sentiments also functioned to reinforce the British empire’s civilisational superiority through advancing the rhetoric that mui tsai girls were the “hideous stain” tarring the sanctity of empire (according to the Hasslewoods). Thus, Lieut-Colonel John Ward, in a House of Commons debate, called the mui tsai system “a disgrace to the British Empire.” Empire’s moralising mission to rectify Chinese stasis and degeneracy allowed it to monopolise a moral high ground. The mui tsai’s bodies became instruments to mark empire’s moral distinction and pre-eminence—they justified the Europeans as overlords over the protection of vulnerable “oriental” women.

Moreover, the missionary forces that took up the task of rehabilitating the mui tsai were less motivated by the religious altruism of benefaction, than by a zealousness to civilise the margins of empire. One documented case occurred in the Home for Slave Girls in Yunan, Southern China, which was founded by the British China Inland Mission. Not only did the Home often prefer able-bodied girls to those with health conditions and physical ailments, they were expected to spread the gospel once they were older and became the missionary mainstays in China. A Sister Maria Wehrheim even expressed her wishes to bring one of the girls’ home “for our household [duties]”. Life in these houses were often just as trying as their previous ones. In Xiamen, at the Society for the Relief of Chinese Slave Girls, a house set up by a local Chinese Christian, multiple mui tsai were reported to have fled the Home in its initial founding years, despite the purported security and comfort offered for the destitute mui tsai. The mui tsai’s supposed liberation merely released the girls into yet another form of harsh regimentation and asceticism, rhetorically cast as training centres to produce good Christian women for missionary work.

The mui tsai’s stories point out a particular dilemma in writing history. Accounts of mui tsai often vacillated between two narratives— either they were subjugated slaves or liberated humanity. Little is left to write a history of their own existence. The term ‘mui tsai’ is a descriptive label that renders legible the figures of Chinese child slaves in history. But it is also a label which already performs the work of disfigurement. To render her presence visible as mui tsai is an acknowledgement that her narratability is only possible as a subject marked and constituted via the colonial encounter.

Narrating her life stories is necessarily a narration of her stories as seen through the gaze of missionaries, colonisers, and of the patriarchal, phallogocentric order monopolised by colonial Hong Kong elites. Repeatedly and violently grafted onto contradictory discourses of indigenous customs and colonial modernity, the mui tsai’s presence was largely dictated by the contours of dominant debates. The power of discourse dictates that her form, her presence and her voice are recognised only through her binary construction either as enslaved subject or liberated agent. Historians should be cautioned against a naïve reconstruction of the mui tsai’s distressed existence.

Sources and Additional Readings

Anti-Mui Tsai Society, 1922. Manifesto of the Anti-Mui Tsai Society. Available at the LSE Women’s Library Archives.

Bradley, J., 2011. The Colonel and the Slave Girls: Life Writing and the Logic of History in 1830s Sydney. Journal of Social History, 45(2), pp. 416-435.

Carroll, J. M., 2009. A National Custom: Debating Female Servitude in Late Nineteenth- Century Hong Kong. Modern Asian Studies, 43(6), pp. 1463-1493.

Haslewood, H. L. & Haslewood, C., 1930. Child Slavery in Hong Kong: The Mui Tsai System. 1st ed. London: Sheldon Press.

Jaschok, M., 1994. Chinese ‘Slave’ Girls in Yunnan-Fu: Saving (Chinese) Womanhood and (Western) Souls, 1930-1991. In: M. Jaschok & S. Miers, eds. Women & Chinese Patriarchy. London: Zed Books, pp. 171-195.

Pomfret, D., 2008. ‘Child Slavery’ in British and French Far-Eastern Colonies 1880–1945. Past & Present, 201(1), pp. 175-213.

Sinn, E., 1994. Chinese Patriarchy and the Protection of Women in 19th-century Hong Kong. In: M. Jaschok & S. Miers, eds. Women & Chinese Patriarchy: Submission, Servitude and Escape. London: Zed Books, pp. 141-167.

White, C., 2014. “To Rescue the Wretched Ones”: Saving Chinese Slave Girls in Republican Xiamen. Twentieth-Century China, 39(1), pp. 44-68.