Gnarly and luscious rainforest trees on pavements cut down, leaving only their stumps; cones and barricades of red and white hue lined up on roads in succession like a parade; corrugated blue fences enclosing a huge land area; slender cranes; as well as crews of foreign workers in safety vests and helmets. This visual description can only mean one thing in an ever-developing Kuala Lumpur – that construction work is underway. Such is the scene along Jalan Hang Jebat (formerly Davidson Road) today, where it would be hard to miss the ongoing construction of Menara PNB 118, a megalithic tower which, upon completion, will be Malaysia’s tallest building, ranking fifth in the world. At RM5 billion, the megatower drew widespread controversy due to the historic value of the site that it obliterates.

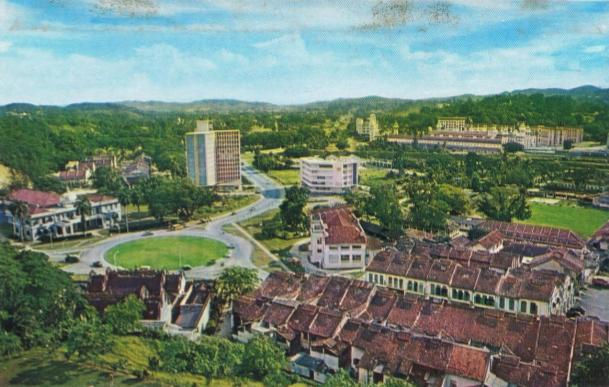

Situated atop Petaling Hill, this 36-acre land was once the site of Merdeka Park. The historical significance of Petaling Hill to the nascent Malay(si)an nation can hardly be understated. The site was viewed by our founding fathers as an urban promontory that would symbolise the egalitarian and secular values upon which the country was founded. Shortly after Independence, sports stadiums, schools and parks were built around Petaling Hill in a bid to create a new public ideal fostered through the collective experience of sports, recreation and education. Merdeka Park was the paradigmatic example of this grand nation-building effort.

Initially named after the nation’s first prime minister who conceived of the project, Tunku Abdul Rahman Park was later renamed Merdeka Park. On its official opening day in 1958, which coincided with Hari Raya festivities, Tunku uttered that the park would be “for all people, for all posterity.” It seemed almost certain to the people in attendance that the park would last for generations. A plaque was unveiled and a tree was planted to commemorate the auspicious day. Some 400 underprivileged children were invited for a party at the playground in the park to join the fun.

Merdeka Park also boasted sports ground for football, hockey, tennis and rugby. Besides that, the park was also home to a set of artificially ornamented miniature caves, and the iconic Merdeka Sundial (now relocated to Planetarium Negara) which doubled as a slide for kids. It was a popular venue among children, friends and families; countless photos capturing memorable and sweet moments were taken there, including some captured by my grandfather.

At the centre of the park was an iconic mushroom-shaped bandstand that resembled a gigantic open parasol, which stood as a fond reminder of the drizzly Merdeka morning on 31 August 1957. Coincidentally and humorously, a mushroom is called dong gu in Cantonese and Mandarin, mirroring in pronunciation the royal title of Tunku.

Before Merdeka Park and the sport stadiums were built, the land was home to the nearly 36-acre King George VI Coronation Park. Like Merdeka Park, King George VI Coronation Park was initially conceived by Selangor’s British Resident Mr S. W. Jones for sports and recreational activities. It was then “Malaya’s most up-to-date sports ground,” with eighteen badminton courts, eighteen tennis courts, seven basketball and netball courts, a bowling green, a children’s playground and a bandstand. The park was also used as a venue for exhibitions and cultural activities such as yuet kwong wui or moonlight rendezvous during the Mooncake Festival.

During ground levelling works when constructing Coronation Park, an abandoned Cantonese cemetery was discovered. Some 900 graves were reported to have been found; the remains were dug, sealed in urns and reburied. In addition, before Coronation Park was constructed an even larger area on Petaling Hill was turned into the 9-hole Petaling Golf Links which, under the Selangor Golf Club, eventually opened a new site on Jalan Tun Razak (formerly Circular Road) till this day. Land on the hill had also been used for Kapitan Yap Ah Loy’s tapioca plantation prior to the golf links.

Change is the only constant, a conspicuous process in the rapidly expanding geography of Kuala Lumpur. Increasingly, more people are moving into the suburbs, and newer parks and recreational areas have been built to replace Merdeka Park. In 1990, when Tunku passed away, Merdeka Park also saw its gradual demise. Around that decade, its site was slated to be replaced by something grander and more economically yielding in the name of development.

Having been born in the 1990s, my impression and knowledge of Merdeka Park has only been mediated through images, writings and audios. I know for a fact that I will never have the chance to experience the space like my grandparents did. In being able to see these photographs from my grandfather’s collection, however, I have inherited a memory that can live on and extend into the future.

Merdeka Park was built in a period of national history briefly after the nation achieved self-governance, and it captured the secular-nationalist direction we were accelerating towards. These photographs, culled from my grandparents’ collection, are repositories of what mattered for a different generation. As my grandmother regaled me with stories of her days spent on dates with my late grandfather, I couldn’t help but imagine them strolling among the stylish urban crowd in these public spaces for the masses. Stories of preservation are fixated with the scale of the megalith: PNB 118, Merdeka Park, Petaling Hill. But in these photographs, a different reality located in the quotidian emerges: of mushrooms, of languorous days at the park, of stories transmitted between generations.

Sources:

RAHMAN PARK | The Straits Times, 1 March 1958, Page 5

A party for slum kids | The Straits Times, 16 April 1958, Page 6

Park opened for games | The Straits Times, 24 June 1958, Page 14

Building Merdeka | Lai Chee Kien, Page 12 – 13, 27 – 33

The Merdeka Interviews | Lai Chee Kien and Ang Chee

Premier To Open Park | Singapore Standard, 16 April 1958, Page 5

Merdeka Park KL Facebook Page | https://www.facebook.com/pg/aparkforallpeople/posts/

Rakan KL Facebook Page | https://www.facebook.com/rakankl2012/

Merdeka Stadium and National Stadium – the fifth injustice and disservice in a week to the memory and legacy of Tunku on birthday centenary commemoration – Cabinet and not PNB should designate them national heritage and monuments | Lim Kit Siang | http://www.limkitsiang.com/archive/2003/feb03/lks2094.htm

Kuala Lumpur’s New Park | The Straits Times, 15 August 1940, Page 14

K. L. WILL HAVE MALAYA’S MOST UP-TO-DATE SPORTS GROUND | The Straits Times, 21 August 1938, Page 14

Fun of the festival | The Straits Times, 2 October 1955, Page 11

K.L. PARK READY SHORTLY | Malaya Tribune, 20 May 1940, Page 3

10 things you might not know about Malaysia Day (VIDEO) | Ida Lim | https://www.malaymail.com/news/malaysia/2018/09/16/10-things-you-might-not-know-about-malaysia-day-video/1673107

Why The Fuss Over Merdeka Park? | Reclaim Merdeka Park | https://reclaimmerdekapark.wordpress.com/why-the-fuss-over-merdeka-park/

HISTORY | The Royal Selangor Golf Club | https://www.thersgc.com/history/

Kuala Lumpur Street Names | Mariana Isa and Maganjeet Kaur