Its striking bright yellow and blue labels are hard to miss. As a frequent shopper at local supermarkets and provision stores, the brand Cocorex is a household name that has continued to build for itself a fairly strong presence in the Malaysian market. For those are not familiar with the brand, Cocorex is known for its range of sodium hypochlorite-based bleach that claims to kill 99.9% of germs.

Now owned by Goodmaid Chemicals who is also its manufacturer, Cocorex traces its beginnings to a local manufacturer that first started out producing cosmetic products for the average local market. The name is of this manufacturer is Choong & Co. And along similar lines, the cosmetic products Choong & Co. manufactured were once distributed in towns and cities in Malaysia.

It was the Trade Exhibition season in Kuala Lumpur again. Held at the Bukit Bintang Amusement Park, fondly referred to as BB Park, the venue was Kuala Lumpur’s most popular venue for nightlife in the mid-century. The Exhibition was a valuable opportunity for businesses to showcase and demonstrate their product range and services. For Choong & Co. who participated, it was their face powder, Eau De Cologne, hair cream and talcum powder that formed their offerings.

The Exhibition was where one would find themselves spoilt for choice by the categories of consumer products available for sale to purchase. Others probably enjoyed the mere sensory experience of being surrounded by what was new and what was trending. Allowing oneself to be tickled by marketing gimmicks, what proved to be more amusing was perhaps thinking that one could outsmart those commercial tactics.

Those who attended the Exhibition would be able to vividly describe the “yeet-lau” or boisterous atmosphere there, on top of the fancy lights and hand-painted advertisements that bedazzled the scene, each vying for attention. By 8pm, the crowd had begun to grow and reached its peak. Unannounced, a certain fragrance was permeating through the humid evening air and was most prominent at Choong & Co.’s booth. To one’s fascination, the scent was coming from a three-tiered fountain with a small distributor on its top.

“My father installed a fountain on top of our booth, to decorate it. And during peak hours, fragrance was added into the water. This attracted a lot of visitors. At regular hours, it was just plain water. The fragrance could be smelled from far.”

Tan Sau Chan, eldest daughter of Tan Pok Chong (Founder of Choong & Co.)

Choong & Co.’s booth at the 1956 Trade Exhibition in BB Park.

The fountain, positioned on the top left corner of the booth, went well with Choong & Co.’s booth design. The aesthetics of the booth represented the directness and functional quality of a mid-century modern structure. Minimal in ornamentation, it embodied what an onward-looking cosmetics and perfumes manufacturer in the capital of a nascent nation should want to communicate. This facilitated attention from the crowd to be directed towards the list of products under the manufacturer’s own brands that were on display, neatly stacked. One of such brands was Moonlight, or in Cantonese: Yuet Kwong Pai.

The side profile of a lady with luscious wavy hair lends itself as an inspiration for Moonlight’s logo. This goes to show that its core target market was women. It also suggests a kind of youthfulness, purity and pink health users of its products may achieve. At a closer glance, one might also find resemblance of this logo to that of the Sam Fong Hoi Tong face powder (a Hong Kong brand since 1933 that is still in production today). Meanwhile, the word “Moonlight” did well to reinforce an association of its products under the brand with an ancient folk belief that the moon or moonlight is symbolic of one’s impeccable beauty.

Behind the counter was a band of dedicated staff members who attended to every customer enquiry and request, making the sales of Choong & Co.’s products successful. Choong & Co. was definitely in it to win it, the merriment doubled when its booth was awarded a prize for Best Decorated Booth which added popularity and good publicity to its name.

A group photo taken at the booth

Prize winners at the 1956 Trade Exhibition

The 1956 Trade Exhibition was one of several of its kind Choong & Co. participated. Others included the 1954 Federation of Malaya Trade Exhibition organised by the Chin Woo Athletics Association, see photographs below.

And in 1962, an Exhibition at the Great World Amusement Park in Klang.

Choong & Co.’s moonlit success story did not begin in 1956.

In 1932, a new chapter of Tan Pok Chong’s life had unfolded when his only option was to leave his job as an apprentice cook at his father’s restaurant. It would not have been an easy decision to make but it was one of necessity, as a consequence of Tan’s father who had debts to settle. The sum must have been considerable, or else Tan’s father would not have resorted to selling off the restaurant, including some other properties owned.

It is speculated that Tan Pok Chong had relatives or friends already in Malaya. With the aspirations for greener pastures like many of his peers and those before him, he found a job at a local provision shop and worked for 5 years, earning $3 per month. Though Tan Pok Chong may be physically in a new land, as a sojourner, a migrant worker, and an overseas Chinese, he continued to remit 90% of his monthly salary to his family back in China – 10 cents from his savings would be used for a haircut. This habitual gesture stood for his filial piety and his unbroken relationship to his homeland, despite he would later settle in Malaya and granted citizenship.

At the recommendation of a Punjabi man who owned a textile business somewhere near Malay Street and Java Street, Tan Pok Chong was a offered a job to peddle textiles in a bicycle around town. He would also later venture into sewing and selling Sarees in Kuala Lumpur. During the festivities, he would set up a stall at Batu Caves.

After the surrender of the Japanese, there was a wide public outcry to the banana notes that became demonetised, many became penniless and financially challenged. With a sum of money amounting to roughly £30 (though it was more likely to be $30 Malayan Dollar), Tan Pok Chong was considered lucky to say the least. While the nation was recovering from the effects of war, he found himself dabbling in selling salted fish and dried prawns obtained from Pulau Ketam. He also sold textiles at Foch Avenue or what locals would refer to as Tze Teen Kai, where the sound of customers haggling was known to be the daily common. It was also roughly during this time in circa 1947 that he would eventually meet and get then married with the love of his life – Liu Lian Ying, whose foster family was then trading red wooden clogs nearby.

Following that, Tan Pok Chong began selling shoe whitener for school shoes made from Bak Lai (white clay in Cantonese or Kaolinite) found at a site in Cheras near where he lived. Producing these shoe whiteners, or Hai Fun (literally shoe powder) involved processing and compressing of ingredients into the intended shapes and sizes. While one tong or tub cost about $10, individual pieces that had to be dried out in the sun were sold at about 50 cents per stack of 12, cheaper than in provision shop or European goods shop which retailed at 10 cents per piece, as Tan Pok Chong’s wife recounts.

Two large tinted glass jars bearing the Polak & Schwarz, Essence – Fabrieken, Zaandam • Holland label – one contained sediments of the fragrance concoction Amber 20 Extra; and the other Mei Zo Shan flower oil. These jars allude to Tan Pok Chong’s acquaintance with a French salesman-cum-supplier who introduced him to the methods of manufacturing another kind of powder: talcum powder. Following those instructions and with Tan Pok Chong’s determination to explore and examine, the business witnessed prospective earnings. This marked the beginning of Choong & Co. and a promising prospect that demanded hardwork and persistence.

The late 50s was an exciting time. Not only did the nation gained independence, Choong & Co. moved its operations to No. 171, Imbi Road, a modern shophouse that could accommodate the scale of production the business was at. From a number of old photographs, it is understood that before this, Choong & Co.’s office was located at 55, Imbi Road, with its factory at No. 3655, Cheras Road.

The location at No. 171, Imbi Road meant that they were neighbours with renowned local restaurateur Madam Kwan whom then had just started running Sakura Beauty Salon at No. 169. While Madam Kwan was well-known for her homecooked nasi lemak which she occasionally served as a treat for her clients, it was her asam fish head that got the Tan family most enamoured. Madam Kwan would subsequently convert her beauty parlour into Sakura Café and Cuisine in the late 70s.

Liu Lian Ying and Madam Kwan were good friends. Both of whom also shared many similar admirable qualities – both played strong, indispensable leadership roles in managing their business and provided for their family. One can probably very easily compose a picture of the duo sharing beauty and facial care tips over casual conversations considering they were both in the beauty industry. In addition to her busy schedule at Choong & Co. – largely being in charge of matters relating to manufacturing, staffing and a list of other tasks, occasionally, Liu Lian Ying would drive her children to-and-fro school. Regretfully, sacrifices had to be made in order to sustain the business which went hand-in-hand with having to make a living to provide for the whole family. Tan Pok Chong and Liu Lian Ying rarely had the luxury to spend leisure family time with their children. This was due to the sweat, blood, and tears devoted to work.

Choong & Co. saw its range of products most popular among middle to lower-income groups; those who could afford more tended to prefer the “more glamourous” European cosmetics. Tan Sau Chan remembers that salespersons were hired to sell their products to provision shops and retailers at various towns, most notably in Ipoh and Johor Bahru. Such outstation assignments involved long hours of driving and stayovers stretching days.

Some years later, the business moved to Brickfields at No. 7 (?) Jalan Abdul Samad, opposite a kindergarten. Up to this point, whenever the business shifted, the family home would shift too as it was a common practice to live above where one’s business is.

By 1969, Choong & Co. had moved to a factory lot at Seksyen 51A, Jalan 225 in Petaling Jaya, near Humes Industry. In the factory was a badminton court where the siblings would spend many evenings playing badminton at. While at this location, a majority of factory staff were comprised of girls from Sungai Way who would cycle their way to work. Though many processes were mechanised, the managerial side of the operations continued to rely on Tan Pok Chong and his family.

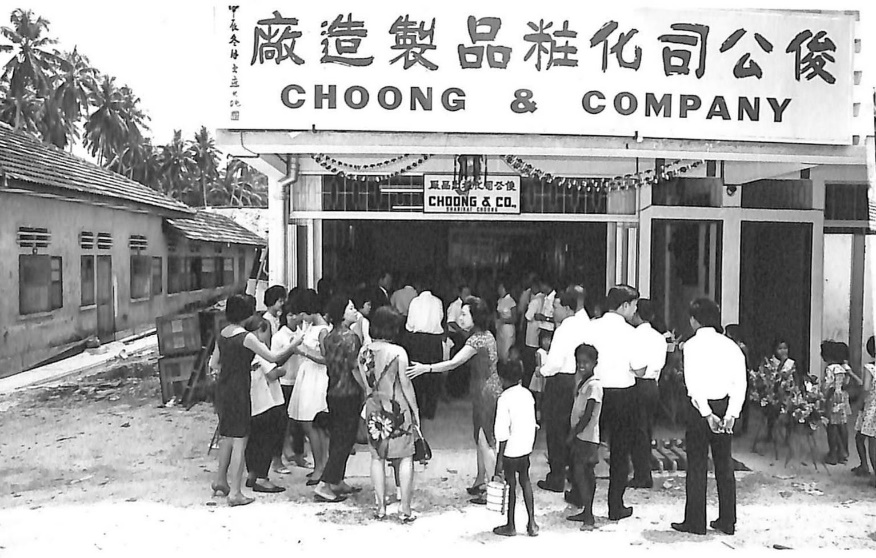

Choong & Co. (Syarikat Choong) in PJ.

Syarikat Choong, as it was later registered as, ventured into manufacturing bleach, something entirely unrelated with beauty and skincare. The brand was Cocorex. A cash cow product for the business which saw most of its sales to be from East Malaysia and Brunei, all shares of the brand were sold to Goodmaid Chemicals in the 1980s. Cocorex may have become a thing of the past for Choong & Co., however, the brand continues to dominate many Malaysian households to this day.

A company van bearing Cocorex’s visuals.

Alongside Choong & Co.’s operation was Plastictecnic (M) Sdn. Bhd., a venture into manufacturing plasticware. This was likely in tandem with a gradual rise in demand for plastic products. As a plastics manufacturer, Plastictecnic (M) Sdn. Bhd. produced plasticwares like containers for their clientele with the likes of Nestle and Dutch Lady. This was during a period when giving out plastic bowls and plates etc. as free gifts were a crowd pleaser. In short, these were promotional plasticware free gifts. Furthermore, plastic pegs were also very profitable, and few in the market then were manufacturing them – Plastictecnic was lucky to be have been one of them.

One of Plastictecnic (M) Sdn. Bhd’s vans parked in front of an entrance of its premises.

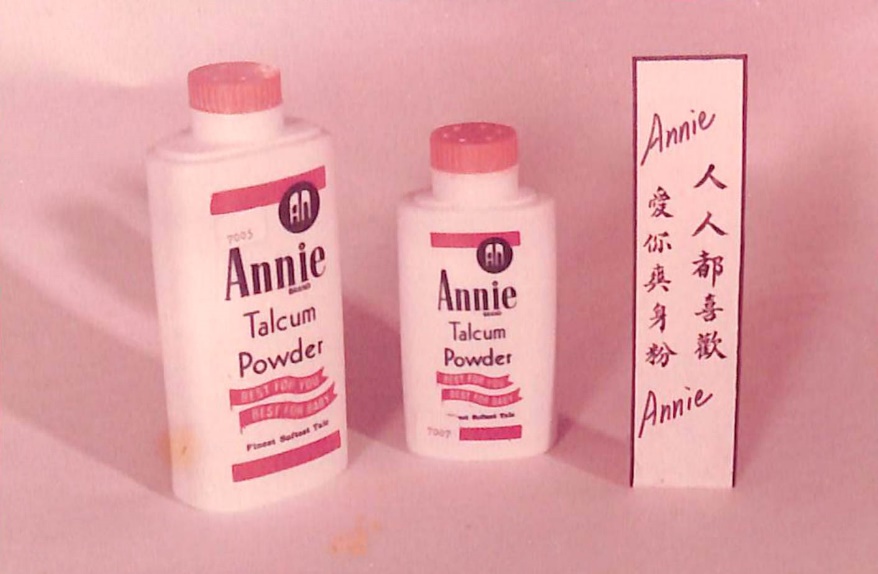

Choong & Co. saw a decline in locally made cosmetics and perfumes with a steady penetration of larger international brands in the consumer market which coincided the growing middle-income class in Malaysia. Locally produced cosmetics became out of trend. Nonetheless, it would continue to introduce cosmetics brands like Annie and Mimosa that met the demands of their shirking market. See photographs below:

The Annie Talcum Powder.

The Annie pancake makeup.

The Golden Flower Talc Powder and Mimosa Stick Deodorant among other products.

The same van depicting its portfolio of cosmetics.

Choong & Co. had eventually ceased producing cosmetics and perfumes when Plastictecnic (M) Sdn. Bhd. moved its premises to a full-fledge plastics factory in Bangi. This spelled the beginning of a new era as Tan Pok Chong and Liu Lian Ying gradually approached a later part of their lives. From humbler days of “hot rice mixed with chicken egg, lard and soy sauce” for meals to days of manufacturing cosmetics, perfumes and household products in a factory, Choong & Co. has indeed come a long way to celebrate the success they have had.

“The fragrance that was used then [by Choong & Co.], I still some of it, and I am very happy to have finally found a use for it now. I tried to put it in a diffuser and it works! You know, just mix it in small amounts with some alcohol. Then, the whole room smells really good!”

Tan Meng Teik (Tan Pok Chong’s youngest son)

People say a scent brings back memories. And sure enough, the remaining essences have found a similar use to evoke nostalgia while setting a room to possibly smell like it did in the 1956 Trade Exhibition. This piece of family history stands as a starting point for us to question how consumer habits have evolved and how that influences businesses to respond. Choong & Co.’s story is a fairly typical story but one that is embedded with the Tan family’s aspirations and countless years of perseverance and naturally, conflict and resolution too. One thing is for sure, consumer trends will always change and all businesses are subject to it. As cliché as it may sound, innovation is key to business resilience.

This article is dedicated to the late Tan Pok Chong and Liu Lian Ying.

Special thanks to Tan Meng Keong, Tan Sau Chan, Tan Meng Teik and Jessica Tan of the Tan family for having so generously shared a piece of their family history with us.