I haven’t been in a prayer shop since I was in primary school. My mum had told me to buy some joss sticks while she went off to the Chinese medicine shop. I remember being confused—the piles of joss sticks stacked too high, an imperious Guan Gong wielding Crescent Blade staring down at me, the ash and dust rendering the store in a slight haze, the Chinese uncle with his satay fan reading the Sinchew at the glass counter next to 80 sen neon coloured lighters.

Right next to his grey head: A tear-off Chinese calendar with its recommendations of auspicious and inauspicious dates, with at least 3 days still half ripped, kangkong green jagged edges left behind.

Now, more than ten years later – in another kampung baru, in another prayer shop – I was buying joss sticks again. I turned to the young man at the counter wearing an Avengers t-shirt and asked him in Cantonese: “What should I buy for people I am not related to but want to pay respects to anyway?”

He handed me a neatly bundled mix of joss sticks, white gold, and various prayer papers that was conveniently labelled “Ancestors”.

“For Hungry Ghost, right?”

I nod. I pull out a stack of 50 sen coins from my zhap fan (or economy rice) stash and pay him.

“Can I use the toilet here by the way?”

He leads me to the back. There is a giant altar there with more than 20 Tua Pek Gong figures. He tells me to pay my respects lest I offend the gods with a bout of bodily profanities, gesturing for me to bow my head low. I bow and proceed to the restroom.

There are 3 moths on the ceiling, still but for the slight wavering of their wings.

When I was 6, my mother told me that the dead sometimes come back to visit in the form of moths. I was a strange kid, spending my time catching insects in the garden and pitting them against each other in discarded sirap bandung cups a la Gladiator. After she told me that, I stopped catching moths but would sit outside on the ground, next to the small red altar, and talk quietly to them.

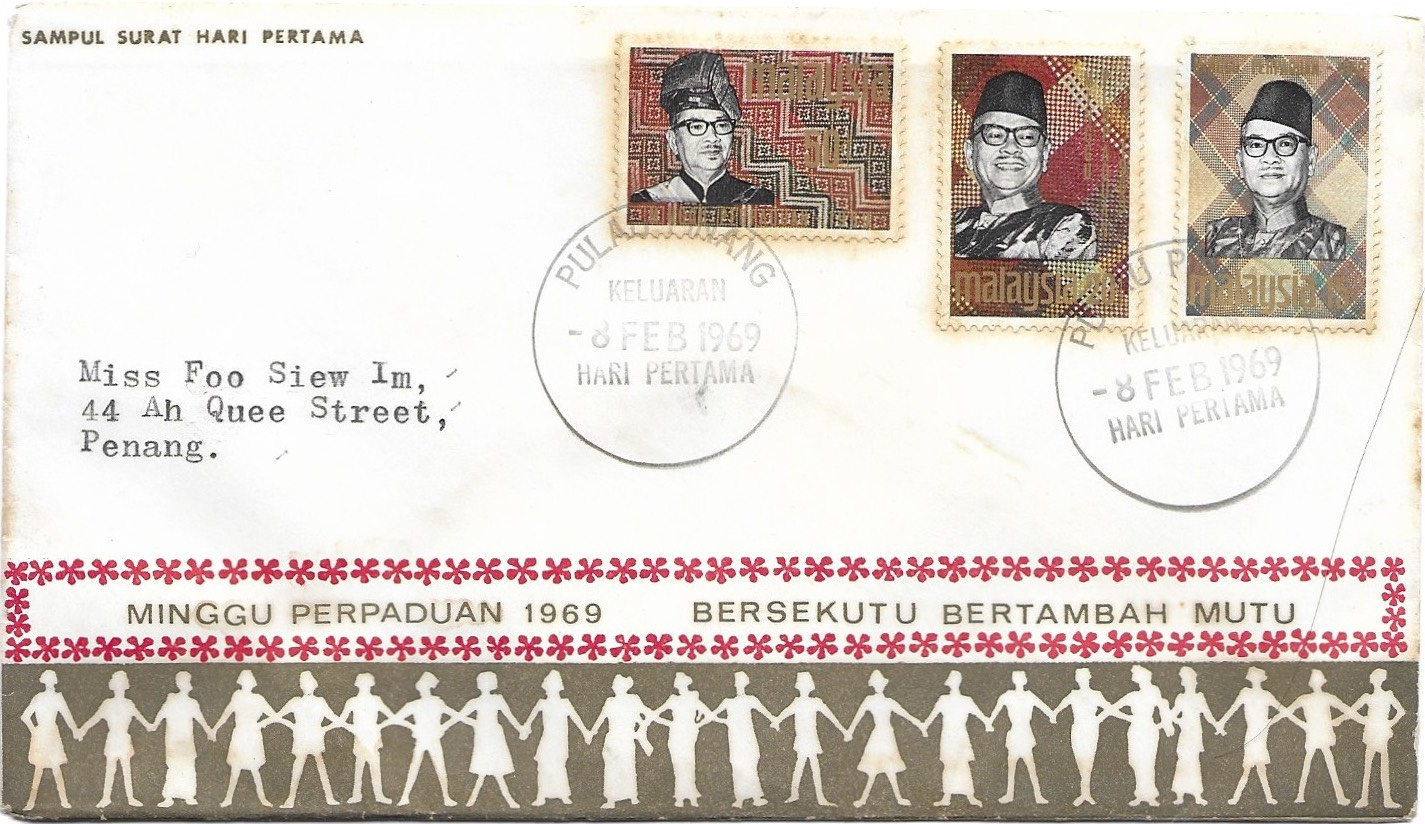

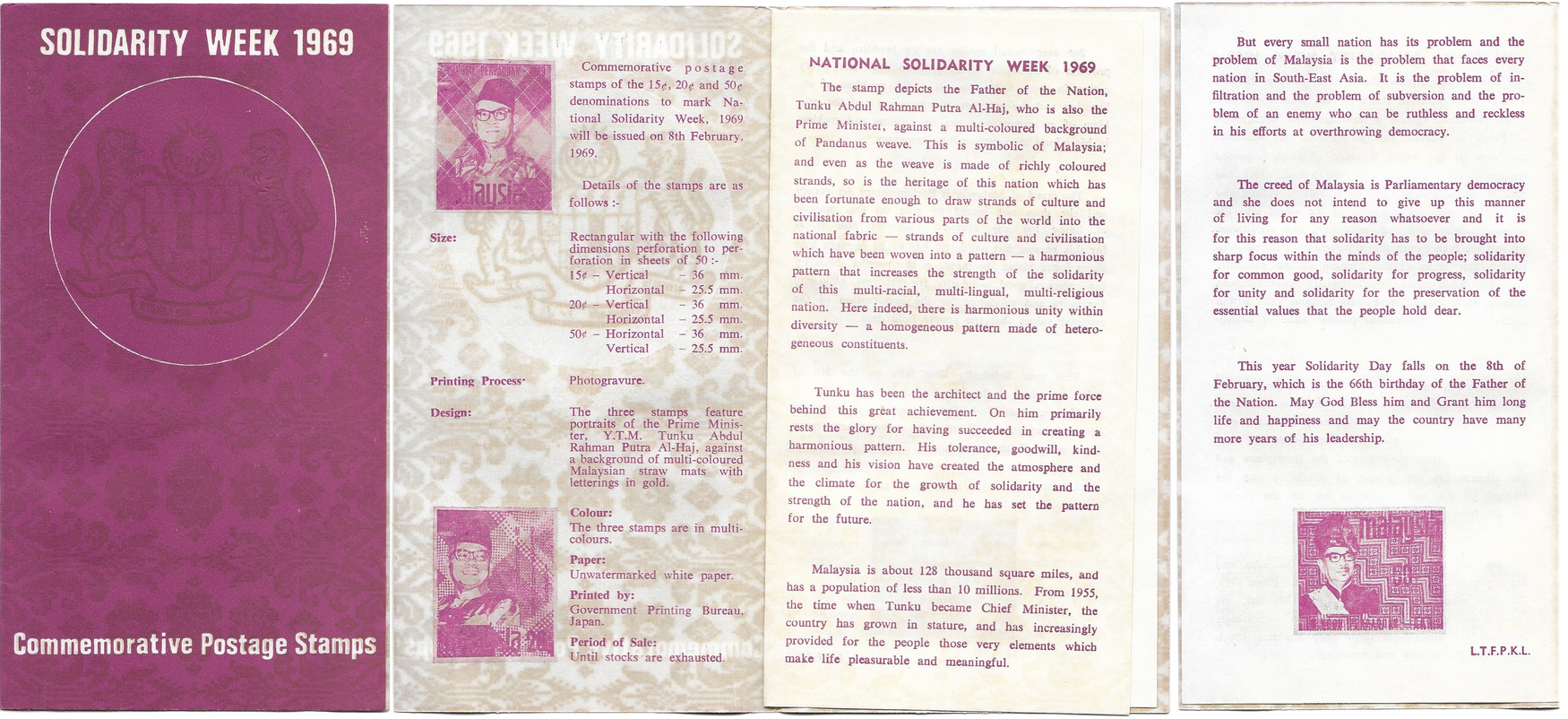

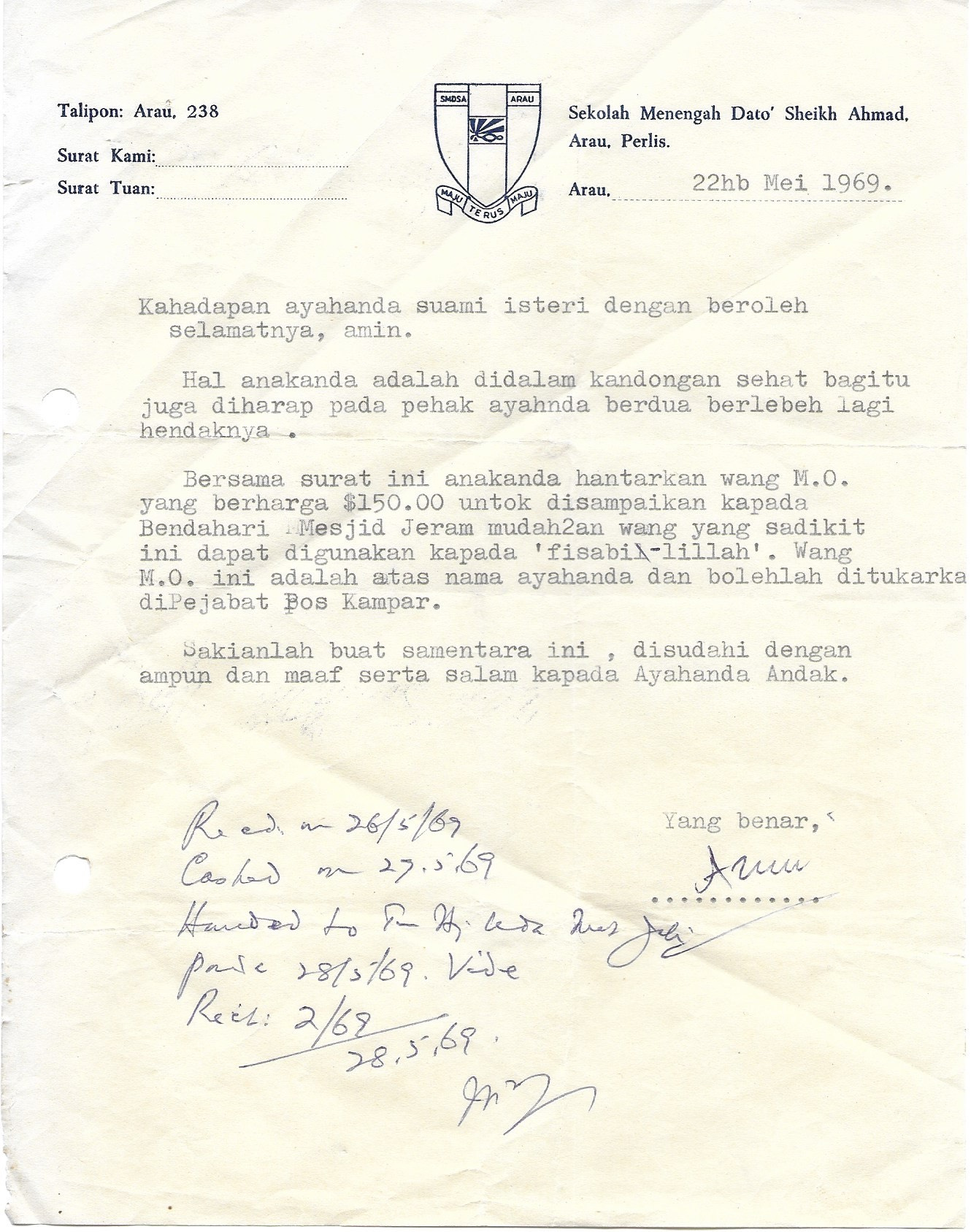

A brochure within the envelope explains:

NATIONAL SOLIDARITY WEEK 1969

The stamp depicts the Father of the Nation, Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra al-Haj, who is also the Prime Minister, against a multi-coloured background of Pandanus weave. This is symbolic of Malaysia; and even as the weave is made of richly coloured strands, so is the heritage of this nation which has been fortunate enough to draw strands of culture and civilisation from various parts of the world into the national fabric—strands of culture and civilisation which have been woven into a pattern—a harmonious pattern that increases the strength of the solidarity of this multi-racial, multi-lingual, multi-religious nation. Here indeed, there is harmonious unity within diversity—a homogenous pattern made of heterogenous constituents.

Tunku has been the architect and the prime force behind this great achievement. On him primarily rests the glory for having succeeded in creating a harmonious pattern. His tolerance, goodwill, kindness, and his vision have created the atmosphere and climate for the growth of solidarity and the strength of the nation, and he has set the pattern for the future.

Malaysia is about 128 thousand square miles, and has a population of less than 10 millions. From 1955, the time when Tunku became Chief Minister, the country has grown in stature, and has increasingly provided for the people those very elements which make life pleasurable and meaningful.

But every small nation has its problem and the problem of Malaysia is the problem that faces every nation in South-East Asia. It is the problem of infiltration and the problem of subversion and the problem of an enemy who can be ruthless and reckless in his efforts at overthrowing democracy.

The creed of Malaysia is Parliamentary democracy and she does not intend to give up this manner of living for any reason whatsoever and it is for this reason that solidarity has to be brought into sharp focus within the minds of the people; solidarity for common good, solidarity for progress, solidarity for unity and solidarity for the preservation of the essential values that the people hold dear.

This year Solidarity Day falls on the 8th of February, which is the 66th birthday of the Father of the Nation. May God Bless him and Grant him long life and happiness and may the country have many more years of his leadership.

Is there inflation in the underworld?

I’m burning the prayer money on the gravel road. Would this be enough for all the graves here? Am I supposed to fold them first or else they get stuck in the afterlife postal service for some technicality?

I placed joss sticks in threes at several parts surrounding the graveyard, lifting them up and rocking them back and forth before struggling to plant them into the dry grassy ground. What was that supposed to do?

It took us almost an hour to find the cemetery. It was conveniently marked out on Google Maps but the directions there were frazzled, leading us on a steep dirt road past a grumpy man and his three aggressive dogs.

“Cari itu kubur ah? Bukan sini lah. Lepas masjid, kiri.”

He clearly had been annoyed by similar intrusions before.

Then weaving through rows of palms and keladi gajah and banana trees along the nursueries of Sungai Buloh, we reached a barricade.

“STOP. CHRISTIAN CEMETERY. TRESPASSERS WILL BE PROSECUTED.”

Sheau stayed in the car while I ducked underneath the bar and walked down the winding road. Phone held to joss stick presentation height, eye trained on the little blue arrow of Google Maps, I kept on going up the hill for another 5 minutes. I passed the red destination dot several times, confused because I saw no gravestones.

“Would you like to use Google Live View?” my phone prompted.

Clicking yes, the screen changed into a view of my front camera.

“Live View uses Augmented Reality to display virtual signposts and directions.”

“Point your camera at buildings and signs across the street.”

It was useless. There was nothing around me but grass.

But there it was on the screen—made visible by the strange discrepancy between real life colours and rendered hues—a grey tombstone emerging from thick wild tall grass behind a kangkong green perimeter fence.

There are more than 100 headstones apparently.

In 2017, there was a ‘rediscovery’ of the May 13 cemetery. News outlets including hip viral ones such as Cilisos covered it, Subang MP Sivarasa proposed it be made a national heritage site, a memorial service of multiple religions was held, interviews were conducted, research was done, ink was spilt, the graveyard was cleared and cleaned, May 13 remembered.

I tried going in, opening the fence. But the grass was too thick and tall and when I pushed through tiny thorns scratched my hands and face. I cut my finger on one of these thorns and exited.

For the next half an hour we simply burnt the paper money on the road while I suckled my bleeding finger.

We left without knowing any of their names.

Day 0

Leading up to the 1969 elections, we had a student manifesto. At the time we university students were very active in politics and we saw the election period as a time when we could demand the attention of politicians to listen to us. In the manifesto, we called for the politicians to endorse the need for a minimum wage, free education, to honour freedom of speech, and to abolish the ISA. Hah! Not so different from the same issues we have now, but I suppose the same generation that were students then is the same people making noise about these issues even today.

We mobilised ourselves and went on a rombongan everywhere. We had a truck, loudspeaker system, we had permits, and drove all over the country—Penang, Ipoh, Kuantan, Seremban—to distribute pamphlets and campaign. I feel like we did make an impact that election; it was not a coincidence that the government cracked down on the student movements after 1969. We were definitely at least partially blamed.

I remember the day itself well. I was actually in town at the Rex Cinema watching the 2pm matinee show. Yeah, we used to call them matinees back in those days.

When I got out of the cinema it was so quiet. Eerily so. Got on my motorbike and rode back to Jalan Pantai Dalam where the university dorms were. By the time I got back it was already 645pm and at 7pm a curfew was imposed.

As it turns out it was orientation or very early in the semester or something and I was caught as one of the few upperclassmen in the college with 150 freshmen. Everybody was hungry because the cooks couldn’t come for their shift, so we went to inspect the food supplies in the kitchen. Even then, we were prepared for the worst so we went about systematically rationing out the food.

I remember looking out the windows and seeing all around the university just towers of smoke. At close to midnight, we got an emergency call from the hospital for all the students to go there and donate blood. That was how desperate they were.

We only got back to our dorms a few days later.

– M. Lim. 15 May 2019 in Penang. Interviewed in person.

Day 4

Day 9

I was in Form 1 then and we lived in Kampung Ghandi, PJ. My father had retired the previous year and we moved from an estate in Batu Tiga and my father bought the land and constructed a big wooden house to cater to big family. He used his retirement benefits to build the house.

During the fateful days following May 13, for a couple of days and nights, we could hear people singing Allah Hu Akbar especially at night very loud and there were intense rumours that the Malays would hunt down the Indians living in the kampung as all our neighbours were Indians. One of my brothers was bold enough to defy the curfew and put all the ladies and children into his car and drove using all the shortcuts, at late night and took us to our relative’s house in Sea Port Estate near Sungei Way.

We only took our clothes and nothing else. We lived in an abandoned worker’s kongsi there and my relative would cook for us and provided us lunch and dinner for few days until my parents were able to source for cooking utensils and started cooking.

My parents then looked for a house in the same estate and bought over a house from someone as by then, the estate became private and workers could keep their houses. We started life afresh and lived in that house for many years until development took place and the estate was demolished making way for Section SS5.

As we had abandoned our kampung house and our family did not want to move back, apparently my brothers sold off the house at a very cheap price.

– R. Madesan, 8:53a.m. 22 October 2012. Interviewed via email: Ong Kar Jin.

2 months, 7 days.

At the time, I was 15 years old and living in Kampung Baru, where as you may know, the violence began. There was a road separating the Chinese quarter of Kampung Baru with the Malay quarter of Kampung Baru.

When the violence began, we were very afraid. We could hear shouting and screaming coming from the other houses. A mob of Malays had crossed the road and they had headed straight for the bungalow directly facing the Malay quarter. The soldiers were actually helping the mob. The house belonged to a Chinese businessman and his family. They were murdered that day. Being rich and Chinese was not a good position to be in. Women and children gone.

In those days, most of the gangsters were Chinese. I had been extorted by them twice before and had learned to avoid them and their gang wars, but the Chinese gangs united and went out with cleavers, sharpened pipes and machetes. Many of them came back on stretchers bleeding and missing limbs. While most of the gangsters were fighting with the mob, the rest of them evacuated the village starting with the elderly, women and children.

We managed to sneak out under the cover of night and get to the Chinese Commerce Chamber or something along those lines. It was a sturdy, well fenced place but there were so many of us and almost nothing to eat. I remember there was only porridge, more water than rice, and with no salt. One of the older Chinese boys invited me to get some chicken. By that, he meant stealing a chicken from back at Kampung Baru.

It seems so stupid now, but I actually followed him. We managed to catch a chicken and we were trying to slaughter it when a soldier grabbed me. He was Sarawakian by the looks of him, and he told me that I was lucky he was not from the Peninsular or I would be shot. He let me go and I scurried away. I think I had escaped death.

– K.S. Chiang, 7:15p.m. 24 October 2012 in Ampang. Interviewed in person.

3 months, 22 days.

6 months.

I can distinctly remember discussing 13 May with my father on three occasions.

The first was when I first picked up a book by Kua Kia Soong on the subject. He looked at me then and said it would be a bad idea to read it. I insisted. He repeated himself and said that it was a sensitive topic and wasn’t really something to just read for fun. We went back and forth for a few more minutes in the bookstore even as people around us started staring.

He bought it for me anyway.

The second was when I wanted to attend BERSIH. We were in the car driving back home when he told me that he didn’t want me to go, that it would be too dangerous.

“What if May 13 happens again? I am really worried ok.”

I sulked and protested loudly. Insolently, I called him a coward.

“Yes, I am a coward. You know when I was a boy I went to see a temple procession. There was a police escort and some guards to make sure the crowd didn’t get too rowdy. There was a young girl who stepped out of line and wanted to join the procession. Someone hit her on the head and I just remember the blood. So much blood pouring out of her head. I don’t want that to be you please.”

I didn’t attend BERSIH that year.

The third was earlier this year. My father frequents Amcorp mall’s weekend flea market, where he digs around for vinyl records. He had found an original copy of the National Operation Council’s report of May 13 being sold by one of the second-hand booksellers. He messaged me a picture of the book.

I texted him back immediately to help me buy it.

By the time he saw my reply, it had already been sold.