Rickshaw

[rick-shaw]

noun

Originates from the Japanese word jinrikisha (人力車, 人 jin = human, 力 riki = power or force, 車 sha = vehicle), literally meaning “human-powered vehicle.”

Only a few older folks can identify the place pictured in the postcard above as Zamboanga, a city in the southwestern part of the island of Mindanao, Philippines. In the backdrop is the Roman Catholic Church of Zamboanga, bombed during World War II. In the forefront is a jinrikisha, a two wheeled cart usually for one, pulled by an Asian man, barefoot, wearing loose shorts, a simple plain shirt and a turban. The passenger is a white man, dressed in all white with a hat, who we can assume is American as the postcard hails from the American colonial period (1898-1946).

Church, jinrikisha, white man and the Asian puller— they are all gone now. The stories of those who pulled these foreign contraptions are not mentioned in Philippine history books. They are all forgotten. Many may even be surprised that these wretched laborers even existed.

The story of the rickshaw, instead of the more officious and original jinrikisha, in Zamboanga reminds us of how life there was quite different from the capital Manila’s.

The Philippines had just proclaimed Independence on June 12, 1898 when America came in to wrest control of the Philippines. In a mock battle at Manila Bay, Spain surrendered to America despite Manila having been under siege by Filipino revolutionaries. Both Spain and America did not acknowledge the Filipino Government led by President Emilio Aguinaldo. In the Treaty of Paris in December of 1898, the Philippines was bought from Spain for 20 million dollars. This marked the beginning of American rule over the Philippines. The Filipinos continued in their struggle with a new enemy but in 1901 President Emilio Aguinaldo was captured which marked the end of the Philippine Revolution. Thus, the Civil Government under the new colonial ruler, the United States of America, began.

It was in following year, 1902, that American businessman Carlos S. Rivers proposed to bring in the use of rickshaws to Manila, a move which was welcomed particularly by American officials who felt its need for easier movement from home to work. He proposed the importation of the vehicles and 1000 Japanese pullers: in those days, Japan was a source of cheap migrant labor. In response to the Luzon Jinrikisha Company, on 21 March 1902, Collector of Customs W. Morgan Shuster ruled that the importation of Japanese pullers was against the law. The law cited, enacted in 1835, was “An act to prohibit the importation and migration of foreigners and aliens under contract or agreement to perform labor in the United States, its territories, and the District of Columbia.” (Root, 28)

The rickshaws were also met with protests from local Filipinos. Historian Michael D. Pante writes on the Manila rickshaw controversy, explaining how protests came in from the cocheros, drivers of horse drawn carriages, who banded together to be part of the Union Obrera Democratica, the first Philippine Labor Federation. They came out with a statement claiming “Filipinos are not beasts.” Filipino protesters were against the rickshaws for fear of becoming “slaves of foreigners” if they agreed to be pullers. Despite already being colonized, the union drew a distinction (however arbitrary) between being conquered and becoming slaves: to be pulling a white man, sweat running off the Filipino back against an oppressive sun, crossed this line. Of course, there were also economic incentives: jinrikishas would present a cheaper alternative to the horse drawn carriages.

Despite the protests, the company started operations on May 24, but only with 20 of the 300 rickshaws, and with Chinese coolies employed as pullers. But Pante continues that “on the second day, no puller reported for work, and the following day, only one did so.” This was possibly due to the “pressure from the Manila Chinese community (many of them from the merchant class) which felt humiliated by their compatriots who chose to be pullers.” (Pante, 144) In the end, the rickshaw business failed to take off in Manila.

Down south however, a different tale unfolded in Zamboanga.

Unlike other Asian cities like Singapore and Hong Kong, which used Chinese coolies, “Moros” or “Pagans” were employed in Zamboanga.

Under the new American colonial rule that came to Zamboanga in 1899, Moros and Pagans belonged to the newly created Bureau of “Non-Christian Tribes.” The non-Christianized usually referred to those that had lesser contact with earlier Spanish colonials, including ethnic groups in the northern part of the Philippines, the un-hispanized indigenous groups (pagans) and those that practiced Islam in Mindanao (Moros). The wide umbrella term of Moros included the Bajau or Samal Balangingi, Tausug, Magindanao, Maranao, Kalibugan, and Yakan. They were considered “uncivilized” and were therefore segregated from the civil government. This Bureau was tasked with the making of “systematic investigations with reference to the tribal peoples… with special view to determining the most practicable means for bringing about their advancement in civilization and material prosperity.” (Forbes, 276)

It was with the patronizing colonial lens of the White Man’s Burden that Major John P. Finley, Governor of the District of Zamboanga, Moro Province, wrote his article on “Race and Development by Industrial Means among the Moros and Pagans of Southern Philippines.” In the piece, he discusses the jinrikisha in Zamboanga.

Finley stated “industrial cooperation led to the introduction and successful operation of jinrikishas by Moros and Pagans at Zamboanga in 1906.” He juxtaposed the Moro and Pagan reception to the Filipinos in Manila. Of the 500 carriages introduced there (in Manila), much was “destroyed by rioting Filipinos, who were enraged against the Chinese for pulling the carts and competing with their native ponies in hauling the quilez and carromato.” He continues: “The Filipinos also pretended to resent the proposition that they should be employed as horses in pulling Japanese carriages.” (Finley, 361) Part of a colonial treatise offering an explanation as to the “backwardness” of the natives and prescribing policy suggestions, Finley dismissed the union’s protests against “becoming beasts” as mere excuses to stave off competition.

In the capital of the Moro Province, Zamboanga, the Moros and Pagans “deliberately agreed to operate such carriages.” We can only surmise the reason why they agreed to be pullers. As Zamboanga is situated at the tip of the peninsula, almost all settlements are located along the coastal areas: travelling from one place to another was usually by boat, the banca or the prahu. Travelers would pay to be brought from one coastal town to the other. The boats were rowed, using manpower. During the American colonial period with the population rising, there was need for transportation to go around the town. What is the difference between using one’s arms to row a boat to that of pulling a carriage? Possibly, for the Moro, they did not look at the work of a puller as demeaning. The act of pulling a rickshaw could have been no different from paddling a boat to take passengers from one place to another. We can only speculate; the experience and the issues of the Moro in Mindanao was different from that of the Filipino in Manila.

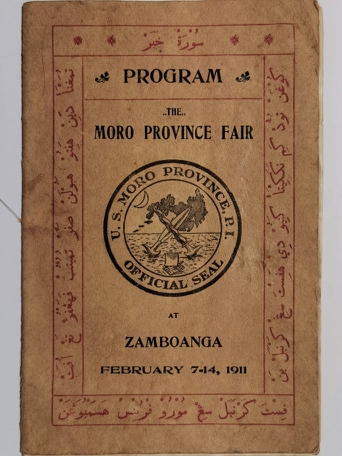

Five years later, in 1911, the First Provincial Fair was held in Zamboanga. “Representative delegations from all the different districts and tribes peaceably assembled together for friendly intercourse.” (Annual report of the Governor of the Moro Province for the Year ending June 30, 1911) For 8 days, from February 7 to 14, various activities were lined up for the more than twenty thousand visitors from different ethnic groups, categorized by Americans as “moros,” “pagans,” as well as (Christian) “Filipinos.” Industrial exhibits and agricultural products were on display and exchanged.

Interestingly, among the different activities in the program, aside from the speeches, parades, dances, and sports contests, were also races. On the 14th of February, was a galore of exciting contests of speed: by goat-cart, pony, carabao race, bicycle, and others, including a three-legged race and a sack race for children. Topping the list was the jinrikisha race! Unfortunately, we do not have photographs of the race, but we can imagine the sight of lean but muscular coolies, sprinting at full speed with all their upper body strength to carry the carriage, and leg muscles to pull it to the finish line.

The printed program for this 1911 Moro Province Fair listed its different attractions. To get around, one could avail of the jinrikishas for 30 centavos (100 centavos = 1 peso) per hour. It was the cheapest means of public transportation – compare this to automobiles at 5 to 8 pesos an hour, Victorias (An elegant carriage drawn by a single or two horses) for 3 pesos an hour, calesas (horse-drawn carriages) for a peso an hour and bicycles for 40 centavos an hour.

Five years later, in 1916, there was another printed program, this time for the East Visayan Athletic Meet. The price of hiring the rickshaw had gone up to 40 centavos for the first hour with 30 centavos for every succeeding hour. From these fairs, we can judge that the rickshaws had become a cheap alternative transport as well as a cultural attraction of Zamboanga—defying the curse of the Manila rickshaws.

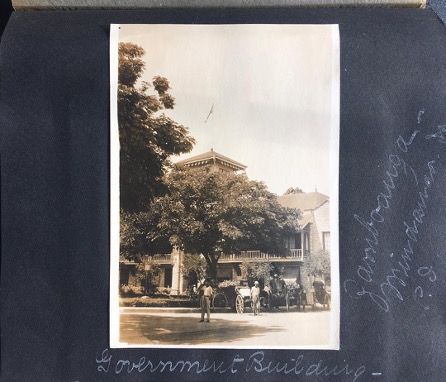

The photo above is from the collection of Glenn Whitman Caulkins, once US Education Superintendent for Mindanao and Sulu. The photograph is labeled as the Provincial Building. Built in 1906 as the seat of power for the Moro Province, it is barely visible behind the large tree in front of it. However, not labeled, but clearly visible under the shade of the tree, are parked rickshaws with their pullers standing by, probably awaiting passengers from nearby establishments. There they stand, clearly visible, yet unacknowledged, and hence unlabeled. The attraction is the Provincial Building, the seat of power, and the rickshaw pullers are there to serve the needs of notables, but otherwise undeserving of mention.

Mertie Heath, a young bride who had joined her husband assigned to Zamboanga as an adjutant of the American army, wrote in 1910 to family back home of her experience riding the rickshaw:

“Had a brand new experience going down to the dock. I rode in a rick-shaw, with a Moro between the shafts. They are plenty in Zambo town, rickshaws I mean, but I had never ridden in one before. It wasn’t bad, Charlie told him to go “poco tempo” and it was only about four blocks from home, so I didn’t feel sorry for him. They trot along usually though, at a good round pace.”

Mertie and Charlie, 2.

Mertie used the abbreviation ‘rickshaw,’ and describes the puller as a “Moro,” indicating that rickshaw pullers were not Chinese, unlike elsewhere in Southeast Asia. And yet, she felt a certain guilt, hastily professing empathy: “it was only four blocks so I didn’t feel sorry for him.” She felt she had to explain to the readers of her letter, who might have disapproved of her riding in the carriage as the puller was not a beast, but human. The language Charlie used to instruct the puller was probably Chavacano. Poco tempo, he says. Meaning, go slow in Chavacano, rather than ‘little time’ in Spanish, which would otherwise be understood as ‘go quickly.’

Unfortunately, aside from these documents, we have no records or lists of pullers, or what their lives were like. Where did the rickshaws come from? Who imported them to Zamboanga? What was the arrangement with the pullers?

If this occupation was reserved for “moros and pagans,” why was this so? Who were they? Were they the Samal Balangingi or the Bajau who lived by the coasts of Zamboanga, or possibly from the village of Magay? Or did they migrate to Zamboanga from nearby areas like Basilanor Sulu? What were the arrangements in terms of pay? I have not found any photo or document suggesting why it fell into disuse. Why did it stop?

I am afraid the photos leave us with more questions than answers. But it is important to ask these questions as they remind us of how little we know about the lives of ordinary people who formed part of the fabric of society in Zamboanga and the Philippines at the time. As with the photo of the Provincial Building, the jinrikisha pullers are still there, even when they remain unlabeled, unnamed, and unacknowledged. They are there.

Sources

1911 Program, The Moro Province Fair at Zamboanga, February 7-14, 1911

1916 Program.

1917 An Official Guide to Eastern Asia Transcontinental Connections between Europe & Asia, Vol V, East Indies including Philippine Islands, French Indo-China, Siam, Malay Peninsula, and Dutch East Indies, prepared by The Imperial Government Railways of Japan, Tokyo, Japan. 1917.

Finley, John P. “Race Development by Industrial Means among the Moros and Pagans of the Southern Philippines.” The Journal of Race Development, vol. 3, no. 3, 1913, pp. 343–368. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/29737965. Accessed 10 Aug. 2020.

Mertie and Charlie (1910-1912), Selected Correspondence of Mertie Beard Heath, An Army Wife in the Philippines, 1910-1912. Compiled by Jessie S. Heath, Canada, Trafford Publishing. 2005.

Pante, Michael D. “Rickshaws and Filipinos: Transnational Meanings of Technology and Labor in American-Occupied Manila.” International Review of Social History, vol. 59, 2014, pp. 133–159. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/26394714. Accessed 10 Aug. 2020.

Root, E., United States. (1898-1906). [Elihu Root collection of United States documents relating to the Philippine Islands]. Washington: Govt. Prtg. Off.

Warren, James Francis. Rickshaw Coolie, A People’s History of Singapore 1880-1940. Singapore: National University of Singapore. 2003.