The Kebaya, with its said origins from the royal courts of 15th century Majapahit Kingdom has come to serve more than the purpose of marking aristocracy in now 21st century Nusantara. ‘The Singapore Girl’ has become the fashionable icon to represent the island-state, always dawning the updated dark purple sarong kebaya designed by Pierre Balmain in 1968 for Singapore Airlines flight attendants. Within Malaysia, the Peranakan women and their distinct stylised ‘Nyonya Kebaya’ have come to exclusively characterise the descendants of Straits-born Chinese immigrants and serve as a symbol for the melding of Malay, Chinese and Indian cultures. Not to mention, the kebaya is the national costume of Indonesia, cemented through constant rejection of the western dressing by Indonesian female prisoners during the Second World War. Today, little girls don a mini version of the kebaya too when commemorating Raden Ajeng Kartini to honour her struggle for women’s emancipation through education on National Kartini Day.

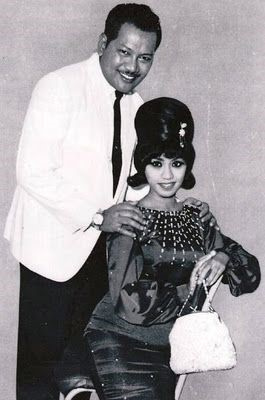

Despite the kebaya being no longer being the everyday wear of people in modern day Malaysia, Indonesia and Singapore, it still serves a particular function within these nation states. Although only one type of many traditional dresses, the kebaya has become a shared symbol differing across these spaces in its construction and standardisation, on top of its characterisation of femininity and cultural identity for a cohesive nation-building narrative. Just as there was a point no elite public figure was more closely identified with the cheongsam and its cultural power than Soong May-ling, the youngest of the Soong sisters of Shanghai who married the Nationalist Party leader Chiang Kai-shek1, there is a salient memory and nostalgia surrounding the kebaya with prominent women of the past pictured in it. Cultural icons from the golden era of Malay film like Saloma, Maria Menado, Chitra Dewi, Titien Sumarni alongside the figures like Hartini Sukarno, Dewi Sartika and Kartini evoking what it meant to be a respectable and educated women then.

Although there are associations of the cut being too figure-hugging, reserved for Peranakan people or seen as Javanese and Sundanese-centric, the kebaya still makes its appearance during traditional holidays, formal occasions, and of course weddings when one is royal for a day. Although there have been several attempts to revive the kebaya back into everyday wear status such as in Jakarta, the Komunitas Perempuan Berkebaya regularly campaigns for #SelasaBerkebaya at Dukuh Atas MRT Station in South Jakarta.2 A similar effort in Malaysia involving discovering the city of Kuala Lumpur through curated public train networks at Keretapi Sarong to commemorate the nation’s heritage on Malaysia day. These events follow in the same vein as My fashion nationalism by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie explaining that she would be wearing only Nigerian-made clothes to represent what is “traditional African” not as static, oriental pieces of artefacts to be kept away in a museum but present it as a dynamic and diverse industry. She also calls it “an act of benign nationalism, a paean to peaceful self-sufficiency, a gesture towards what is still possible; it is my uncomplicated act for complicated times”.3

It is this “benign nationalism” of Adichie reveals arguably how femininity and nationalism are inextricably linked in an uncanny way. Jean Gelman Taylor argued that priyayi men dressed in Western style as heirs to Dutch rulers while women were expected to continue dressing traditionally, representing the nation’s essence and what it meant to be quintessentially Indonesian.4 A similar rule also applied with the Dutch colonial women where they subscribed to the social prescription of white endogamy and “made the custodians of a new morality – not, as we shall see, those ‘fictive’ European women who rejected those norms”5 while the Dutch men’s concubinal relations had worried the state wherein by 1930, 90% of legally classed Europeans were mixed blood mestizos.6

Present postcolonial nation states are no different with the ‘Singapore Girl’ born marking the split between Malaysia-Singapore Airlines (MSA) in 1972, following Singapore’s separation from Malaysia in 1963. The Singapore Girl has gained recognition internationally, gracing all sorts of advertisements with extensive coverage of what it takes to become one — a persona that has extended beyond being a flight attendant. More peculiarly is the recent Peranakan Genome Research Project in an attempt to redefine what being Peranakan means beyond adoption of Nusantara customs, usually signaled by Chinese women in Nyonya Kebayas.

On the other hand, you can always rent a kebaya or just the sarong to capture the epitome of Indonesia at Penataran Lempuyang, in front of a great volcano shrouded in mist. Meanwhile the figure of Raden Ajeng Kartini is just as malleable to the nation state, first made national heroine in 1964 by Sukarno was later repackaged as Mother Kartini Day by Suharto to fit the New Order policy of State Ibuism. Similar is the case of Hari Ibu in Indonesia, made an official holiday on 22 December 1953 to mark the anniversary of the first Indonesian Women Congress in 1928 of which the day of commemoration has changed from a marking women’s first collective mobilisation with the formation of Perikatan Perempuan Isteri Indonesia (PPII/Federation of Indonesian Women’s Organizations) to primarily celebrating motherhood.

For the case in Malaysia, the kebaya ensemble is the crowning glory of multiculturalism with not only the Peranakans of particularly Malacca, harking to its 15th Century Sultanate but also having the “Most Number of Beauty Queens Wearing Kebaya in a Fashion Parade” in the Malaysia Book of Records at the annual Miss Malaysia Kebaya.7 Every so often women in particularly Nyonya kebayas become viral all over the internet, be it doing a kebaya-themed photoshoot with friends at Penang’s Peranakan Museum or this year’s “Peranakan”-inspired national costume for Miss Universe Malaysia.8 The image of Saloma with P. Ramlee also continues to hold its cultural weight as the glory days of not only film but a young Malaysia then, regularly referenced to in pop culture today. So salient is Saloma’s image that the peplum kebaya she regularly adorned in the 60s with flared hips and ankles has been attributed to her, inspiring the modern kebaya in Malaysia today.9

Time and time again, women and national femininity have fallen back on the traditional kebaya with state intervention in attempts to characterise meanings of the country’s heritage, values and cultural traditions while masculinity instead tend to play the modernising force of the nation. Nevertheless, as Barthes argues “clothes are always a combination of a specific signifier and a general signified that is external to it (epoch, country, social class); without being sensitive to this the historian will always tend to write the history of the signified . . . there are two histories, that of the signifier and that of the signified and they are not the same”.10 Imagining and belonging to a community always involves some kind of differentiation from other communities, and as authenticity can rarely be sustained in fashion and us as signifiers can make new meanings of what it means to be a 21st century woman in Southeast Asia shopping for her next open house on Zalora or rummaging through your mother’s closet to match a reused corporate batik tailored for the company’s annual dinner.

Notes

[1] Sandy Ng, “Clothes Make the Woman: Cheongsam and Chinese Identity in Hong Kong.” In Fashion, Identity, and Power in Modern Asia, pp. 357-378. Palgrave Macmillan, 2018, p. 360.

[2] “Women promote ‘kebaya’ wearing at MRT station.” The Jakarta Post, 26 June, 2019. <https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2019/06/25/women-promote-kebaya-wearing-at-mrt-station.html>

[3] Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, “My fashion nationalism.” Financial Times, 20 October 2017. <https://www.ft.com/content/03c63f66-af6b-11e7-8076-0a4bdda92ca2>

[4] Schulte Nordholt, (ed.) 1997. Outward Appearances: Dressing State and Society in Indonesia. Leiden: KITLV Press.

[5] Ann Stoler, “Sexual affronts and racial frontiers: European identities and the cultural politics of exclusions in colonial Southeast Asia.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 34, No. 3 (1992): 514-551, p. 538.

[6] Justus Van der Kroef, “The Eurasian Minority in Indonesia.” American Sociological Review 18, no. 5 (1953): 484-493, p. 484.

[7] Zarina Yusof, Norwani Md Narwawi, Azliza Aris, “Malay Kebaya: The History and Influences of Other Silhouette” in Proceedings of the Art and Design International Conference (AnDIC 2016), pp. 445-452, p. 446; Jade Chan, “Kebaya’s crowning moment of glory.” The Star, 28 February 2019. https://www.thestar.com.my/metro/metro-news/2019/02/28/kebayas-crowning-moment-of-glory

[8] Melanie Chalil, “Former TV3 broadcast journalist and friends go viral for fabulous kebaya-themed farewell photoshoot in Penang.” The Malay Mail,17 July 2019. <https://www.malaymail.com/news/life/2019/07/17/former-tv3-broadcast-journalist-and-friends-go-viral-for-fabulous-kebaya-th/1772365>

[9] “Peplum pilihan terkini baju raya.” Astro Awani, 6 August 2013 <http://www.astroawani.com/gaya-hidup/peplum-pilihan-terkini-baju-raya-19841>, “Minimalist look the ‘in thing’ in fashion this Hari Raya.” The Borneo Post, 9 June 2018 < https://www.theborneopost.com/2018/06/09/minimalist-look-the-in-thing-in-fashion-this-hari-raya/>

[10] Roland Barthes, Oeuvres Complètes, vol. 1, Paris: Seuil, 1993, p. 743.